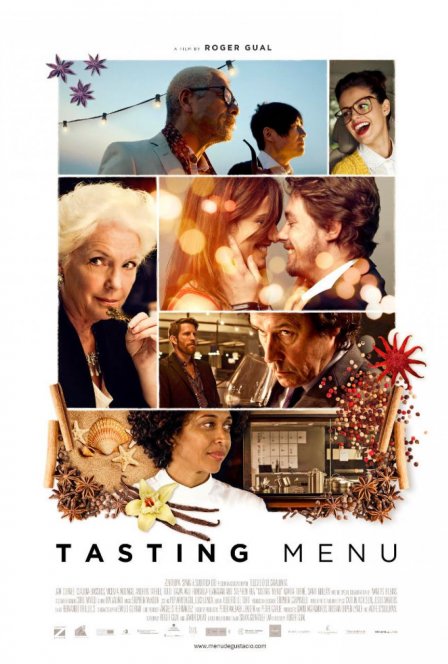

While one in four Spanish citizens currently remains out of work, the depression-mired state of Spain’s total population stands in stark contrast to the global prominence of its high-end chef population. The molecular gastronomy of Spanish gourmet wizards such as Ferran Adrià and José Andrés sparked the current cultural obsession with food and its trappings. On the cinematic side of things, Pedro Almodóvar became a titan of international film by fusing farce and melodrama into a signature style that has earned him largely well-deserved accolades. Taken at face value then, Roger Gual’s idea to film a farcical melodrama set around the closing night of a famed molecular gastronomy restaurant appears a perfect remedy to the doldrums of contemporary Spain. Humor in the face of catastrophe can certainly prove valuable, as the fictional director John Sullivan learned in Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels. Shouldn’t humor that draws on the innovation and success of Spain achieve this? Moreover, Almodóvar himself created an ideal metaphor for the concept of humor set against impending tragedy in his recent plane crash comedy I’m So Excited (TMT Review). Yet humor of this kind requires a light touch to succeed: without the wry social observations wielded by a filmmaker like Sturges or the mastery of the absurd possessed by Almodóvar, a film can barrel straight into the tone deafness of Gual’s Tasting Kitchen.

The film centers on Marc (Jan Cornet), the chief doctor at a pediatric hospital whose personal life has suffered because he is just too devoted to saving those kids, and his estranged wife Rachel (Claudia Bassols), a celebrated novelist whose fast-paced cosmopolitan life clashed with her husband’s career (or something). Back before their separation, the couple made a reservation at the exclusive Costa Brava restaurant for what turns out to be the closing night; for this reason, and narrative convenience, they put aside their (sorta) conflict to enjoy a world-class meal together. While the film dances around the couple’s (sorta) problems as they enjoy exquisite cuisine and free flowing wine, a cast of cultural stereotypes and hackneyed characters play out (sorta) dramas of their own. There are uptight Japanese businessmen and obnoxious Americans, a woman who talks too much, and a man who keeps making mysterious phone calls. At one point in the film, an aristocratic English widow berates her butler, wondering without any hint of irony why she continues to pay him. There is no awareness whatsoever that this is how a terrible rich person would behave. On the contrary, through Gual’s lens, this scene intends to convey the character’s firecracker spirit and razor-sharp wit (silly servants, always making mistakes, know what I mean?).

If anything, Gual unintentionally creates the setting for a perfect “Masque of the Red Death”-style horror narrative or one of Luis Buñuel’s satires of the upper class. Somewhere in the making of his movie, Gual seems to have sensed that, apart from the cartoonishly saint-like Marc, his characters were all more or less horrible people. The film’s climax thrusts the indolent diners into action to rescue a group boaters who were (yes, this is seriously what happens) shipwrecked on their way to deliver the meal’s pièce de résistance for dessert. If it weren’t so blatantly transparent, we might call this a cheap trick. To be fair, it’s not just the people who suffer from Gual’s inept handling. The world of high-end gastronomy is ripe for satire and absurdist humor. Even the chefs who inspired the film seem to get this: the aforementioned José Andrés now serves as the food advisor for the Hannibal series on NBC, crafting beautiful culinary concoctions for the sophisticated cannibal serial killer. It’s too bad a comedy like Tasting Menu lacks that sort of comic sensibility. In the end, Gual’s message to the economically depressed populace of Spain seems to be, “Let them eat nitro foam cake.”