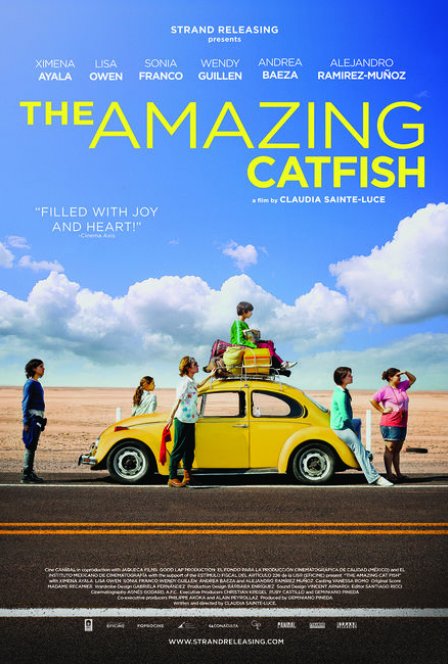

There are the compulsively watchable — those utterly benign movies that go down like so much popcorn or “starting in 14 seconds…” episodes — and then there are the agreeable. As a descriptor and a summary, it’s weak. Yet for The Amazing Catfish (Los Insólitos Peces Gato), a sleepy musing on illness, family, and loss, it’s something of a triumph. Claudia Sainte-Luc’s Locarno Film Festival Entry is good precisely because it doesn’t strive for much. Where its major themes could veer it toward the bathetic, Catfish never enters telenovela nor teen-lit territory. Instead, it is a simple exercise in cinema agradable, avoiding the schlock common to its particular collection of plot points and nixing the equally trite and groaningly self-aware denial of that standard treatment. In this context, it’s a very “nice” film, only relevant because “sick films” so rarely are, and wholly digestible without that someone-will-die-at-the-end (someone does die at the end) reflex/reflux. All its easily serialized miseries — to wit: HIV, dead moms, deadbeat dads, coming-of-age, depression, homelessness, isolation — are treated as footnotes in the greater, if less thrillingly mawkish, story of a modern family.

Claudia (Ximena Alaya) is a disaffected product-demonstrator, hawking sausages by day and squatting by night. It’s a lonely boxcar existence, her only interactions with gluttonous customers and the rumble of talk radio. Acute appendicitis sends her to the hospital, where she meets Martha (Lisa Owen), a full-time mother whose HIV has reduced her hours. Martha’s four children crowd her bed and the screen; they are immediately and undeniably present. There’s Wendy (Wendy Guillén), the overweight jokester with an open interest in homeopathy and a secret one in self-harm. There’s Mariana (Andrea Baeza), the tween narcissist; Alejandra (Sonia Franco), the prematurely put-upon; and the only son, Armando (Alejandro Ramírez-Muñoz), the precocious wit. Martha and Claudia meet over a shared bag of Ruffles and with comically little warning, Martha’s larger-than-life family begins to seep into Claudia’s void.

Claudia’s entrance into their world is an odd transition, reflected in a sudden shift in the air. That is, Claudia’s mournful leitmotif gives way to the purely diegetic soundtrack of familial cattiness. Dialogue is constant and apparently incidental, occurring with improvisational swiftness and tangency. All their barbs and trivialities leave little room to talk about family and plenty in which to be one. What matters is not what they say, but merely that they keep talking. Claudia, an affectless doe (of the “Jane” and deer varieties), came out of her accordion-scored listlessness and into their home, where mood music couldn’t get an e-minor in edgewise. The irregular hum of this anti-Krebsbach household is a welcome alternative to the AM radio that voiced her surrogate mother for twenty-odd years.

And despite its post-nuclear diversity, she’s entered a house full of mothers. There’s the loving but incapacitated biological one. There’s Alejandra’s born-of-necessity killjoy disciplinarian. There’s Wendy carting her younger sibs to school, Armando constantly toting a hamper and laundering towels, and the near-stranger Claudia suddenly making lunches and guiding her ersatz children through adolescence. Then there’s the other mother: the very-felt absence of Claudia’s own. This family, however inclusive, will never be Claudia’s.

As more is uncovered about the characters’ pasts, the details become less relevant. The revelation that the four children come from three different fathers is less engrossing or certainly less endearing than is Mariana’s brush with hairstyling. It’s more absorbing to watch Claudia and the kids do nothing at an office party than to expend too much thought on Claudia’s alluded-to dark past. Martha’s progressing HIV is painful, but the more compelling story is the family surrounding her, going about all the incredibly dull things families do to get by. What is exciting is the surprisingly intricate choreography of this reassembled family. Family itself is the main axis of motion, captured on a camera that barely budges. They navigate their cluttered home like rats in an eccentrically-decorated maze. They weave in and out of frame with the peculiar physics of a family, their paths of motions constantly overlapping and running parallel.

But, in the end Martha dies. Off-screen, of course: an active loss would counter Catfish’s aesthetic trend. Its precious few shots are full, brimming with intimate visual chatter, or promising fullness, with the few frames of solo Claudia merely preluding her coming acceptance. Martha’s death is not a dramatic fissure, nor should it be in a movie that’s very merit is its quiet agreeability. The mother’s parting words are banal — maternal pleas for clean fingernails and well-polished teeth for all her children. It’s nothing special, but it’s a pleasant way to go.