Wealth and domestic bliss, the art of photography, some of the most renowned French actors in modern cinema, everything measured and precise. The Big Picture has a polished veneer that touches almost every aspect of the film. As slick and professional as this is, it’s also something of a necessary ploy. When every strand of a story evokes a memory of some other story, artifice is possibly the best way to get by. In this case, there are so many referents that one could describe the film as Hitchcockian, regressive, or mass market. The ideas are so well-worn that it must be tactful to succeed in its replication.

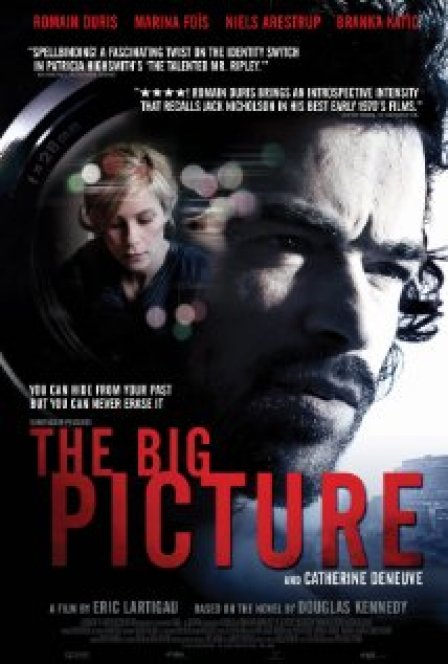

Adapted from an American novel by Douglas Kennedy, director Eric Lartigau moved the plot from Connecticut to France and renamed the protagonist, but the story is universal and, fittingly, emotional and physical transience is its center. Paul Exben (Romaine Duris) is a partner in a law firm (which he shares with Catherine Deneuve, in a minor role) and a father of two with a house large enough for twelve. His life appears to be perfect and he seems in control, but he suspects his wife is having an affair. Before he can accuse her of infidelity, she leaves the manse with the kids in tow. Devastated, Paul confronts who he believes to be his wife’s paramour, and what begins as a tête-à-tête ends in a bludgeoning. With his wife away for a week, Paul has to devise a plan that will cover his egregious mistake.

Paul’s scheme is brilliant and devious, and to give away its intricacies would ruin a tightly coiled sequence that is the pinnacle of this excursion. I will say that disposing of a body always seems to be the most problematic element of a homicide, and Lartigau gives it the full treatment. Clever and cunning, Paul flees the country and rents a shack in the hills of Montenegro, assuming the identity of an itinerant photographer. He warily befriends a drunk (Niels Arestrup, the crime boss in A Prophet, as Bartholomé) who offers him a job as a photojournalist, and his presence in their secluded hamlet becomes more apparent. This second life is at once unfettered and constricting, and Duris handles the dramatic swings with confidence. His anxiety is erratic and palpable, and in his children he has reason to be conflicted about desertion. Coupled with deliberate pacing, the fine acting in The Big Picture upholds what is, from any other angle, a suspenseful beach read.

For the most part, double lives serve as fascinating, if derivative, plot devices. The Big Picture doesn’t transcend its construct — in fact, it fits squarely into the genre. But it goes beyond facile entertainment by exploring the demonstrative vicissitude of its protagonist with conviction. It’s a satisfying thrill ride, though some may balk at its conclusion. I, for one, walked away relatively content.