There’s a particular type of big-budget movie that may not deserve the label of the worst that Hollywood has to offer, but are nonetheless pretty bad. These movies provide little more than sheen, the ones that play all the cinematic notes well enough to resemble movies that have things to say, but, when all their fancy camerawork and “acting” are parsed aside, don’t in fact say much. The Gambler is a classic example of this type of movie, the American (and therefore bigger and louder) version of what François Truffaut decried in French studio films of the 1950s as the “tradition of quality.” Even as the film makes you weary to think about it, the question it makes you contend with is: can a bad movie’s patina of quality ever be enough to fill in its hollow center?

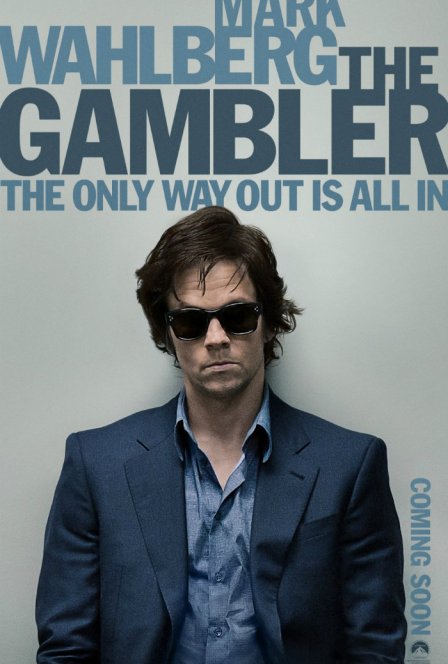

Mark Wahlberg, embodying possibly the worst casting of a career increasingly marked by being miscast as an intellectual, plays published novelist/literature professor/degenerate gambling addict Jim Bennett, a scraggly-haired, perpetually sunglassed rich kid who howls at the unfair universe that gave him every advantage in life save for the immortality of creative genius. He’s a studio screenwriter’s carefully concocted idea of what a human train wreck might look like: charismatically disheveled, barreling down a safely glamorous route of self-destruction. In the opening moments, Bennett is crying beside his wealthy grandfather’s deathbed. After the funeral, which he apparently headed to straight from the hospital, he tears through the L.A. night in his BMW to an underground casino run by a shadowy (and exhaustively stereotypical) Asian mob. There, Wahlberg conveys the reckless abandon of a blackjack addict using the unmistakable tics of the wannabe actor — enunciations and gestures so precise it seems he’s memorized the audition tape of some less bankable star who was passed over for his role — as Bennett gets himself buried in debt to no less than two mobsters in the span of 10 minutes. He staggers out of the casino at dawn and plods off to a college, where the big reveal is supposed to be that this bad man is also teaching a seminar on the modern novel.

As in the original The Gambler from 1974, this narrative conceit seems to make little sense, until you find out that original screenwriter James Toback actually was a gambling addict and literature professor, and until you see the original role inhabited by the far more convincing James Caan. Wahlberg’s acting style as a college lecturer is no less tic-y than what he offered as a gambling addict: he emotes as if on cue, raising and lowering his voice at regular intervals to give the impression that Bennett is going through internal conflict. Bennett’s method as a writing instructor consists of acting exasperated that his students haven’t already given up writing on account of not being geniuses, and it becomes evident as Wahlberg shouts and fusses his way through a rant on artistic mediocrity that the film is trying to draw some comparison between Bennett the failed novelist and Bennett the gambler.

At this point, only three sequences into the movie, The Gambler appears to have shown its cards: in a self-serious way (somewhat belied by director Rupert Wyatt’s neurotic over-stylization), it’s aiming to be a movie about a writer who drowns out his fears of mediocrity with a self-destructive habit. That’s an overdone theme, but overdone doesn’t mean exhausted, and a movie that aims to explore it, even using a movie star who can’t act and a by-the-numbers director to do it, can at least be credited with trying to be meaningful in some way.

And then, as if not satisfied to make a half-hearted attempt at seriousness, Wyatt and screenwriter William Monahan explode their idea of what kind of movie they want The Gambler to be. What was initially a problem of a well-intentioned movie being sabotaged by an ill-equipped star and a twitchy director quickly becomes a problem of a movie with no clear intention whatsoever. As The Gambler moves into its second act, it becomes a hodgepodge of scenes following Bennett around L.A. and Las Vegas as he attempts to evade mobsters and secure cash (by hitting up relatives and/or engaging in high-stakes gambling). At times, his motivation seems, vaguely, to be to ruin himself through gambling so he can be reborn as a man ready to write again; at other times, he seems to simply want to win the affection of his “genius” writing student, the conveniently beautiful Amy (Brie Larson, a good actress showing an unnerving tendency to play the non-descript love interest to indifferent movie stars); by the end, as Bennett orchestrates a scheme to play his debtors against one another and emerge the bruised but still-standing victor, no audience member would be faulted for thinking he or she was watching one of those “who’s conning who?” thrillers that piles on the clever twists but can’t decide on an ending to save its life.

One of the big pluses of the film is John Goodman, as the third and most convincing mob boss to make the ludicrous mistake of loaning Bennett gambling dough. He’s far scarier than the other gangsters, especially in the use of his terrific face; he has gotten much more skilled and less hammy as he’s aged into a grand old thespian of American cinema. But his character, along with the two other Ultimate Mob Boss Badasses in the movie (Michael Kenneth Williams and Alvin Ing) is still made to menace and scowl and cackle evilly while making decisions that absolutely no mob boss (at least not one whose goal was making money) would do. Bennett is at one point cornered in the middle of the street by three limousines, out of which rush thugs who, in broad daylight, shove him into one of the cars and secret him away to a dry pool in an abandoned warehouse, where they tie him to a chair on top of planks of wood covered in plastic. He looks like he is about to become a victim of Patrick Bateman. One of the gangsters he owes money to (Williams, this time) shows up and gets to colorfully threaten Bennett, who is allowed to escape the entire situation with only a single blow to his head, simply by refusing to pay his debt. Why would a powerful kingpin go to such theatric lengths in order to give a guy who owes him $50,000 even more time to pay it? Because he is a character in a movie. How do we know that that movie is not to be trusted? Because that movie asks us to believe it takes place in the real world and then turns around and has mob bosses do idiotic things.

That’s as good an example of why The Gambler fails the seriousness test as Wahlberg’s inability to convey gravity or any of Wyatt’s useless visual flourishes. To make an example out of the last director to defy logic by casting Wahlberg, use this as a litmus test: If you believe that Michael Bay’s crimes against cinema (see the Wahlberg-plays-genius-inventor movie Transformers: Age of Extinction) are lesser because he’s at least honest about making crap, then you may hate The Gambler as much as I did. If you feel that making a movie to resemble an honest examination of human character without doing any of the legwork that earns a movie its dramatic stripes at least winds you up with something watchable, then have at this flick.