Those who have followed the films of animation house Studio Ghibli and its idolized director Hayao Miyazaki (the esteemed animator and storyteller behind Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke, among many, many others) know that Miyazaki’s career has been one built on contradictions. Mostly, these contradictions hinge on two facts. The first is that Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli’s greatest works exemplify the magnificent power of imagination, the sanctity of childhood and close-knit friendships, and the reflective potency and wonder of nature and the pastoral ideal. The second fact is that, in contrast to this magnificent, humanistic, and bucolically pure vision, Miyazaki’s films and characters have become such a financial and cultural phenomenon in Japan and abroad that they have birthed a seeming empire of merchandise and filmic devotion that itself is directly in contradiction to Miyazaki’s magical, Arcadian vision. This basic contradiction, along with a host of companions, is at the root of director Mami Sunada’s documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, which follows Miyazaki and the other founders of Studio Ghibli as they work on Miyazaki’s final film before his long-overdue retirement.

Sunada, whose previous documentary Ending Note: Death of a Japanese Salesman chronicled the death of her father, does a remarkable job of telling the story of Studio Ghibli and its founders as though the documentary were itself a product of the animation studio. All the familiar sights and emotions are there as we wander through the cluttered halls of the Kogenai-based studio: sweetly sentimental and idyllic, and accompanied by piano music that communicates a deep sense of elegance and nostalgia, we see the storied place where fantastical tales are manufactured and perfected. There is plenty of time to look at cherry blossom trees or watch the sunset from the studio’s rooftop garden and feel sweetly remorseful, even as the studio itself is cubicled and in disarray. And like any Studio Ghibli film, a meaningful familial relationship is at the core of Kingdom of Dreams and Madness: the occasionally turbulent brotherhood of Miyazaki and fellow director Isao Takahata, along with their shared producer Toshio Suzuki. In between tracking the process of the creation of Miyazaki’s final film, 2014’s The Wind Rises, the documentary takes us back to the beginnings of Miyamoto and Takahata’s long-standing collaboration, which oscillates between friendship and heated rivalry, particularly as Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya, both created at Studio Ghibli and produced by Suzuki, are due to be released simultaneously.

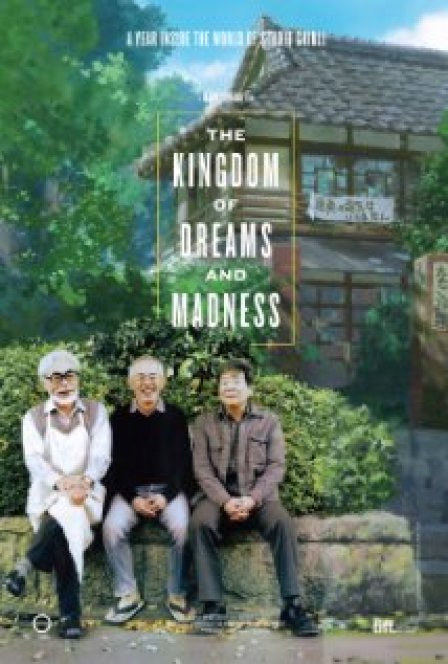

This blending of camaraderie and hostility is typical for the film and for Miyazaki himself, ostensibly the documentary’s de facto star and a man made up of contradictions, betweens, and oscillations. White-bearded and wearing something between a lab coat and an apron — the perfect metaphor for his status as somewhere between an artist and an engineer — Miyazaki is alternately warm, profound, wistful, and terrifying. As one animator says, “The more talented you are, the more he demands… If there’s anything within you that you want to protect, you may not want to work with him.” The film notes that even Studio Ghibli’s free-roaming cat knows to stay away from where Miyazaki works. Yet some of the film’s greatest moments aren’t of anger or unbridled genius, but those in which Miyazaki quietly reflects and wonders aloud. By now an old man who still never stops questioning, he admits at various points that despite making a series of innovative and fabulously successful films (Spirited Away remains the highest-grossing Japanese film of all time), he himself never feels happy in his daily life, and thinks that making films in this day and age is futile — more a hobby than anything else.

This basic juxtaposition — a man renowned for his kind-hearted and optimistic films who himself is deeply cynical about everything the world has to offer — is at the heart of The Kingdom of Dreams of Madness and the basis of many of its most fascinating moments. Miyazaki, an anti-war advocate who is obsessed with warplanes, talks about the contradictions of his father as someone who made money off the war but who was, himself, a generous and compassionate man. Similarly, a poignant sequence of Miyazaki describing Japanese militarism in the 20th century is juxtaposed against a frivolous cosplay-laden comics convention and conservative political rally. We see the collocation of a merchandise-oriented business meeting and the surreal sight of animators all doing calisthenics together. And at one point, a business-suited Ghibli representative speaking to a group of prospective employees states, “We value friends, I guess…”, then pauses and rethinks, before saying “I don’t know if the term ‘friends’ is appropriate… but at Ghibli we do value human relationships.” It’s exactly the kind of corporate semantics that could not stand any more directly in opposition to Miyazaki’s humanistic films. These are the kind of problems that exist when a group of people who extol the virtues of nature, simplicity, pacifism, and anti-consumerist creativity become the center of multi-million-dollar international conglomerate.

And that’s what Sunada’s documentary captures so well — the problems and necessary hypocrisies that accompany the experience of making art in the 21st century. It’s a film about the manufacturing of purity; about a workspace that creates end-results that are magical and nostalgic, but is itself cluttered, work-heavy, and overlooking an electrical plant. It’s kind of stuff perfectly encapsulated in the moment when Miyazaki completes the storyboard for The Wind Rises, and celebrates by popping a fake bottle of champagne, complete with a button that shoots the cork off. And yet the experience of watching the film somehow doesn’t leave one disillusioned. For like any good Miyazaki film, that feeling of loss and darkness — this time the loss of a pastoral and creative ideal — is offset by a warm sentimentality, timeless companionship, and bittersweet nostalgia.

And thusly is Miyazaki sent off. One of the film’s sweetest moments is watching Miyazaki draw, entering a sort of biomechanical space where he repeatedly flips a piece of paper up and down, opening and closing his mouth without making a sound, timing his gestures with a stopwatch, and sometimes muttering phrases to himself over and over: “What is it? What is it? What is it?” This perfect balance of artistry and mechanics carries on in sacred silence, until Miyazaki awakens from it, says, “This is tedious. I quit,” before getting up and quietly walking away.