The epistolary novel “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” first published when I was the same age as Charlie, its hero. He is a quiet, sensitive boy who cares more about English class than the other kids, and who develops friendships with a group of misfit seniors. When I read the book in freshman year, I could relate to Charlie better than most readers, I imagine, and he’s a character who’s designed to be universal. So when I heard author Stephen Chbosky wrote and directed the film adaptation of his book, my first question was, “Why? Why wait more than a decade to turn your book into a movie?” The answer, to my pleasant surprise, is he must have been waiting for the right actors.

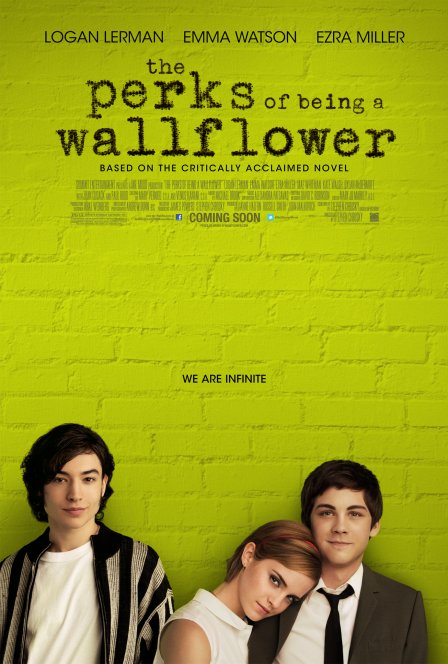

Chbosky wisely abandons the narrative structure of his book. Through voice-over, we hear excerpts from the letters Charlie (Logan Lerman) writes to his unnamed “friend.” On his first day of high school in a Pittsburgh suburb, his classmates ignore him or they’re casually abusive. He’s the sort of kid who knows the right answers, but is too timid to raise his hand. In shop class, a loud senior named Patrick (Ezra Miller) brazenly mocks their teacher (horror legend Tom Savini, showing his hometown pride). Charlie introduces himself to Patrick at a football game, where he also meets Patrick’s step-sister Sam (Emma Watson). Patrick invites Charlie to a diner after the game, and Lerman wisely underplays Charlie’s joy. The scene is sweet and heartbreaking in equal measure.

Chbosky follows Charlie and his new-found friends throughout the school year. They go to parties, experiment with drugs, and share mixtapes that aren’t so tiny. The screenplay elegantly weaves sub-plots into major high school events. Patrick has a secret affair with a football jock, for example, and they must play the roles required of their respective social strata when others are watching. Despite all the standard tropes of a coming-of-age story, it’s the smaller moments where the movie finds its heart. In brilliant performance, one that couldn’t be more different from We Need to Talk About Kevin, Miller goes over-the-top as a way of guarding his vulnerability. He would steal the show, but his affection for Charlie is real. Watson has a trickier job. Charlie loves Sam, but she puts Charlie firmly in the friend zone, only to find romantic feelings later. The transition is seamless; when Chbosky goes for an emotional crescendo, there won’t be any audience eye-rolling.

There is a unseemly undercurrent throughout Charlie’s freshman year. He hints at a painful secret, and flashbacks to his aunt Helen are weirdly sinister. We learn the secret of in the final act, yet this detail is less effective on screen than it was in print. There is already so much drama from Charlie discovering himself that we don’t need a past to provide a tragic layer of context. Chbosky’s adaption is the most successful when he focuses on the normal travails of high school; seemingly ordinary scenes are given emotional heft through sensitive direction and the finely-tuned performances. Not even a seriously egregious pop culture blind spot undermines the movie. For a major plot point, Chbosky has us believe that a group of aspiring hipsters in 1991 have never heard one of David Bowie’s most popular songs. The song pops up twice in The Perks of Being a Wallflower, and the way it’s used is enough for me to forgive Chobsky’s oversight. If only he had been so shrewd with Charlie’s dark history.