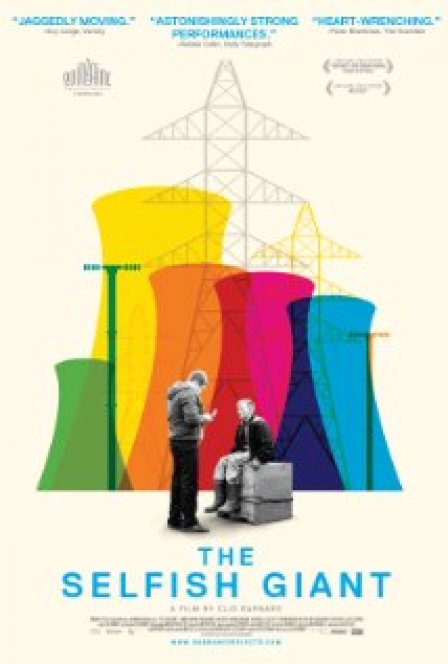

Although loosely inspired by the Oscar Wilde children’s tale of the same name, Clio Barnard’s The Selfish Giant owes more to the social realism of Charles Dickens than the allegorical fantasy of the former. The specter of urban poverty and industrial blight looms over the entire film, visualized by the repeated shots of power plant stacks spewing smoke over an otherwise green pasture. Set in an unnamed working-class town that may or may not have seen better days, Barnard’s narrative centers around young friends Arbor (Conner Chapman) and Swifty (Shaun Thomas). Arbor hails from a broken home with a single mother and a drug addicted brother. Swifty’s life reflects a different version of the same impoverished conditions: an overcrowded house, a father gambles who away what money comes in, and a mother who constantly struggles to put enough food on the table. The “giant” of the title is a cutthroat scrapyard owner named Kitten (Sean Gilder), who, in another nod to Dickens, functions as more of a Fagin character in his exploitation of children desperate to help their families.

At a glance, the boys’ friendship appears to be one of convenience, an outgrowth from the mockery of their peers and their shared place at the fringe of society. Arbor is afflicted by a minor personality disorder that manifests itself in (sometimes entertaining) fits of adolescent rage, while Swifty is a gentle soul who feels a deep bond with horses (albeit one that originated in trips to the track with his father). Their interaction with Kitten only widens this chasm in their personalities: Arbor views the work as a weapon in his fight against the world, Swifty as a means to spend time with the horses Kitten employs for his pull-carts and underground chariot races. The film, however, would have us believe otherwise, suggesting a genuine connection between Arbor and Swifty that stems from how they straddle the boundary between childhood innocence and the problems of the adult world.

Yet the fable-like quality of Arbor and Swifty’s “journey” out of adolescence into the morally gray realm of the adult world contrasts with Barnard’s use of handheld cameras to create a “man-on-the-street” atmosphere of grit and realism. The film manages to convey how easy it is for kids like Arbor and Swifty to fall through the social safety net, how parents who are too busy trying to make ends meet fail to supervise them, and how unscrupulous individuals like Kitten use them to take advantage of loopholes in the legal system. What’s missing, however, is a more thorough examination of the underlying causes at play in this world. Kitten emerges as the film’s most compelling performance, but Barnard never even attempts to examine his character’s situation. Did he start out like Arbor and Swifty and rise to the “top” of the literal and metaphorical scrapheap of this industrial wasteland, or did he simply inherit it? There are feints and hints of salient details, such as his relationship with his wife, but never more than a glimpse into his psyche. His acceptance of his own transgressions towards the end of the film lacks the weight needed to take what should be a sledgehammer to a society that, more than a century after the time of Dickens, still sacrifices children to the altar of industrial (or even post-industrial) capitalism.