In the first 10 minutes of Thunder Soul, we’re convinced of the greatness of a now-defunct band because of the unrestrained, infectious verve we can see (and hear) in its historical records. Then we’re sped forward to the present, or rather to 2008, to catch up with that band after life has happened to it. The movie is overwhelmingly committed to convincing us that everything in the present is just fine, so, as is more common with a fiction film than a documentary, the truth behind the movie has to be inferred by watching its subjects closely.

The one we watch closest is the most badass original member of the Kashmere Stage Band, a little-remembered but once-great 1970s jazz-funk phenom. The badass, Craig Baldwin, has morphed into the group’s spiritual (and literal) leader by 2008, the year the band reunites for a reunion show. The reunion is the subject of this movie, a lively, happy, utterly-in-league-with-its-subjects documentary. According to Baldwin’s own lore, he once stalked the rundown neighborhoods of Houston’s Fifth Ward with his cousins, fighting, smoking, and selling drugs. Thirty years later (the only time we see him, aside from in vintage filmstrips), Baldwin manages to emote a bit of the swagger he lays claim to, but he’s traded in drug dealing and hoodlumming for visiting with his dying mother and encouraging his old band mates to pick their instruments back up and play.

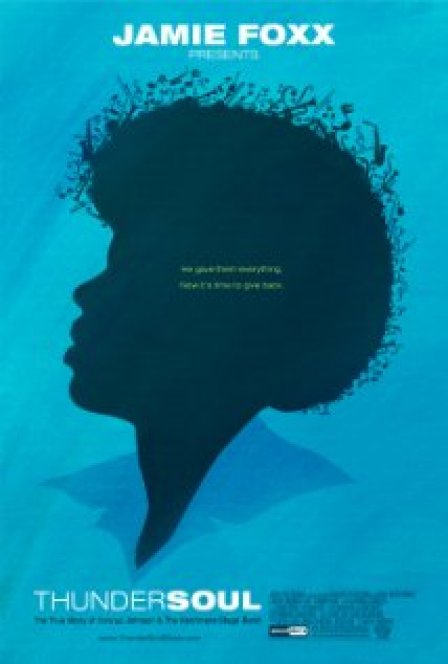

The old 70s swagger was apparently more than just a bluff. Baldwin and the rest of his buddies achieved something — something called high-praise, fame, and a recording deal — at an age when most musicians are too busy plucking around trying to get their notes in key to brag about anything. That is, the members of the Kashmere Stage Band were all in high school. Led by a skinny, charming black man dubbed “Prof” by the kids, they were a simple band class meeting in a high school in East Texas, except that Prof, a former professional jazz musician, was something of a visionary. As the inspirational tone of this documentary repeatedly sounds off, what Prof saw in his class of black teenagers from a Houston ghetto was called musical talent, and he spun it into a world-class band that repeatedly won the All-American High School Stage Band Festival, put out high-selling records, and toured the world.

Prof’s name is Conrad O. Johnson. His own lore is that he grew up into jazz and once had the opportunity to turn pro after playing with folks like Count Basie and Erskine Hawkins. He eschewed the professional route, though everyone (in Thunder Soul at least) maintains he could have been a legendary name in jazz. Instead, he married the love of his life and settled down to inspire youngsters through music. This back story comes, of course, mostly through the youngsters he inspired, only speaking to us while in their mid-50s, the same age as Prof was back when he taught them. So the audiences watching Thunder Soul can easily be forgiven for suspecting that all this lore smacks a touch specious.

Forgiven because, when the band’s kicking, we might not even notice it. Whether Johnson could have been a jazz great or not, what he did inarguably was turn 30 or so high schoolers into a world-class collection of funk musicians, and Thunder Soul’s at its best when peering back in time to reconstruct what they all looked and, more importantly, sounded like. Filmstrips show them with tipsy afros and garish clothing, executing choreographed dance moves while blowing horns. Records confirm what their stage exuberance made visible: they sounded fucking great. For all of its doe-eyed remembrance of faded glory and the unfortunate fact that it focuses mainly on the 30-years-later reunion of Kashmere instead of delving deeper into the band’s heyday to fully flesh out the tantalizing (and lost) 70s culture that produced it, Thunder Soul isn’t misrepresenting the fact that Kashmere was incredible.

Further, every member of Kashmere is now over the hill, and while the doc tries to mine some (unnecessary) comedy out of the rusty musicianship with which they dutifully reengage to put on their twilight concert, one thing the 50-something musicians aren’t rusty at is mugging for the camera. Each and every one of them reached an apogee in high school when the Stage Band briefly got world famous, and each and every one them can hardly contain their eager desire for this doc to catapult them back there. Even Baldwin, the reformed badass and undeniable glue holding the reunion together, seems glibly aware that a camera is recording his appropriately saddened face as he visits a 93-year-old Johnson in the hospital to deliver the news that the band’s back on.

When finally, expectedly, the reunion band gets to play, Johnson is up out of the hospital and watching from the first row. And they sound okay for a bunch of weather-beaten adults fiddling with instruments in a high school auditorium; more than likely, to the ears of a 93 year old, they sound great. When they’ve finished, they’re met with the proud adulation and applause anyone who’s just played in such a venue should expect. It’s a small, happily resigned end to a story that started out on top of the world. You can see where it might’ve been a potent metaphor for the occasionally deflating arc of life itself, if the auditorium’s response weren’t framed by the movie as the resounding victory it wasn’t.