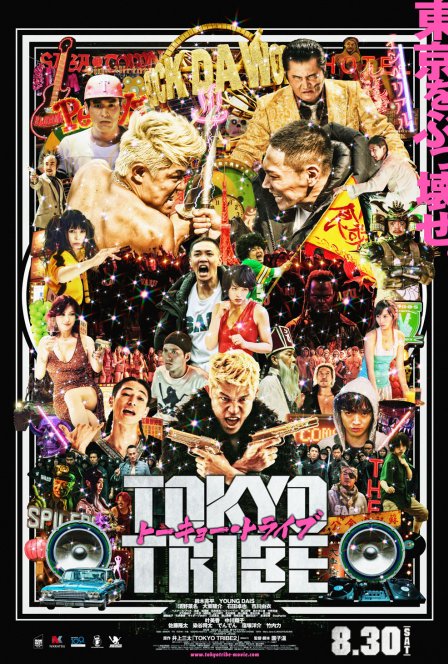

For some readers out there, this might be a pretty simple one sentence review: Shion Sono’s Tokyo Tribe is the director’s hip-hop musical about warring gangs in dystopian Japan. If you’re a fan of Sono, stylized Japanese cultural amalgamations, or manga — the film is a live action adaptation of a series — then that’s probably all you need to know. To unfamiliar audience members, try to imagine if Baz Luhrman and Quentin Tarantino co-directed an apocalyptic, martial arts and rap-infused update of West Side Story after watching Walter Hill’s The Warriors, Brian De Palma’s Scarface and Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers during some kind of a vision quest. That’s probably the closest approximation I can concoct for Sono’s latest release (though by no means the prolific filmmaker’s most recent work).

Set in a version of the title city afflicted by lawlessness and earthquakes, the film chronicles the course of an evening that erupts into full-on gang warfare. Characters are introduced and defined by their rapping. The (allegedly) 23 different gangs are loosely categorized, but the central conflict involves a chill hippie-meets-hipster gang and a power-hungry organized crime gang. The chill folks rap about love and togetherness while hanging out at Penny’s, a late night diner that appears as though the art director and set designer made a slight design modification to the logo of a well-known Americana chain. The organized crime tribe resides in the boss’s mansion, where the godfather likes to fondle a phallic statue behind a globe emblazoned with the words “Fuck Da World”; his son is a sadistic weakling who uses the gang’s sex slaves as furniture, while his senior henchman is a muscular, thong-wearing samurai swordsman with eternally recurring penis size neurosis. I’d argue that never has “good vs. evil” been so oversimplified and so intricately deconstructed for all its complexity in one single work. There’s also a demon priest’s daughter on the lam to avoid her virginal sacrifice with her breakdancing ninjitsu little brother.

So is Tokyo Tribe for everyone? Probably not. Should everyone see Tokyo Tribe? Probably. As an exercise in visual style, the film transforms rap video semiotics into epic poetry. Sono’s tracking shots through the dark, chaotic street scenes create a sense of dreamlike futurism, with occasional bursts of surreal imagery such as a man bathing himself in viscous goo for no apparent reason. An elderly grandma DJ spins from a street table, while the hoodie wearing MC Show (Shota Sometani) guides the viewer in and out of scenes intermittently in a chorus function. Time stamps pop up in scene transitions, as if to remind us of the film’s march towards inevitable tragedy and conflict. Yet for all the sense of predestination Sono conjures up, perhaps the most interesting quality the film suggests are the individual motivations that never quite seem to align into a neat pattern. If a fractured society is the film’s artistic statement, the outright differences between the “tribes” — which never appear quite as distinct as they would like to believe — yields to each character’s individual goal. Despite all the madness, goofy humor, and obvious gestures towards grand themes, it’s actually this more subtle notion that resonates by the end of the film.