If absurdist comedy fails to shock, illuminate, or delight, it just hangs there, like a grimace after a failed joke. The half-baked absurdity that pervades The Trouble with Bliss resides in this limbo, forced but not forceful, serving only to alienate viewers without repaying them in either entertainment or enlightenment.

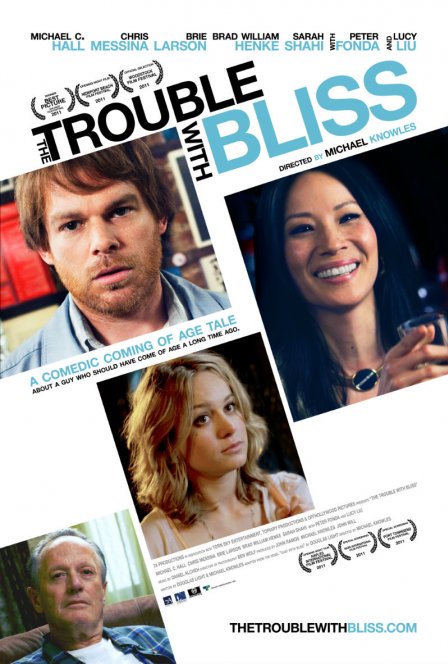

Michael C. Hall stars as a 35-year-old sadsack burdened with the ironically significant name of Morris Bliss. His life is (surprise) anything but blissful: unemployed, he lives with his flinty father (an Eastwood-esque Peter Fonda), who gives him money to buy groceries, which he squanders on cigarettes for Stephanie (Brie Larson), a schoolgirl who picked him up in a record store (the first indication that we’re not dealing with reality here), and beers with his buddy N.J. (Chris Messina), a pathological liar whose yarns grow increasingly outrageous. The world of the film is governed by coincidence: the schoolgirl happens to be the daughter of Bliss’ obnoxious former classmate Jetski (Brad William Henke), who owns a building that has been commandeered by squatters, one of whom (Sarah Shahi) is actually the heiress to a real-estate fortune, who hooks up with N.J., who might not be a liar after all … and so on. The filmmakers have labored to ensure that everything is linked and nothing turns out quite as expected, which is not to say that anything turns out interestingly.

Director Michael Knowles (Room 314, One Night) co-wrote the screenplay with Douglas Light, author of the novel on which it’s based (East Fifth Bliss), but neither demonstrates a cinematic vision for this material. The script contains scarcely a trace of human emotion, yet it makes only one brief, belated foray into outright surrealism, settling instead for a lumpy brew of illogic, irony, and dreaded indie quirkiness. Much of the dialogue, especially in the tone-setting first scene, sounds stilted — theatrical, actually, in spite of its literary origins. Meanwhile, the performances and visual style are basically naturalistic, which clashes rather than contrasts with the precious writing. Late in the film, when Bliss finally breaks free of his inertia, it’s supposed to be an epiphany, but the unearned moment just feels incongruous.

The film marshals its deliberate contrivances in service of a statement about narrative: almost every character tells stories (which are sometimes enacted in cutaways), and N.J. remarks that the quality of a story is more important than whether or not it’s true. Perhaps, but if you expect to get away with that, you’d better have a good story or at least good characters. Unlike the Duplass brothers’ Jeff, Who Lives at Home, which is remarkably similar in setup and theme, The Trouble with Bliss has neither. It consists of scenes that are rarely funny or insightful, involving a cast of pseudo-eccentrics who are too weird to relate to, but not weird enough to be compelling. Least compelling of all, despite Hall’s game effort, is Morris Bliss himself, a drab, unmotivated ball of passivity at the center of the movie. If he doesn’t want anything, why should the audience want anything for him? This film’s efforts to explore apathy succeed only in engendering it.