For over 10 years, a non-stop barrage of soundbytes, images and reports from the Middle East has streamed into our living rooms, computers, phones, tablets and radios. Some of this has been our own doing, as in Iraq and Afghanistan, while other events have occurred more naturally — the still ongoing Arab Spring being the primary example. Behind the developers building the websites where we access the latest updates on each respective conflict, the talking heads that tell us what they think we need to know and the over-produced analysis in cable network “situation rooms,” there are actual people — real human people — on the ground experiencing and documenting the bloody life-and-death struggles of our fellow human beings. Through a screen half a world away it is easy to forget this fact, something Mark Jackson’s new film, War Story, attempts to remedy.

Lee (Catherine Keener), a war photographer recovering from a traumatic experience while on assignment in Libya where her partner was murdered, is holed up in a Sicilian hotel. We quickly realize the titular war here isn’t one of movements, buildups, or winning “the hearts and minds” of a people, rather it is an internal struggle Lee must traverse, one of past demons, regrets, guilt. She cuts herself off from the outside world, ignoring phone calls from colleagues imploring her to return to New York, all the while attempting to come to terms with the horrible acts she has witnessed. Jackson strikes a dark and claustrophobic tone immediately in the film and never lets up. Keener is front in center throughout, the camera rarely leaving her side through close-ups and tracking shots that serve to highlight the paranoid state Lee finds herself in, and by extension, the paranoid nature of a world where conflict is the norm (as the sagacious George Orwell once wrote in his landmark novel, 1984, “by becoming continuous war has ceased to exist”).

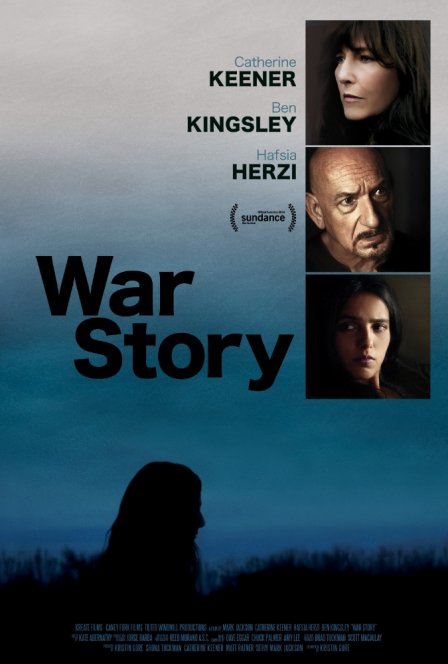

Despite its basis in fiction, the film is important to our continued understanding of the effects these conflicts have on individuals — in this case reporter and subject — especially as they span decades, not just years. But Jackson’s work is not without its flaws. It is left to Keener to carry the film and although she does marvelous work here, the rest of the supporting cast comes off as an afterthought. Sir Ben Kingsley makes an appearance as Lee’s mentor, but he is never given enough screen time to lend the film his considerable gravitas and it is clear the producers simply wanted a second recognizable name alongside Keener to help sell the film. Hafsia (Hafsia Herzi) a Tunisian woman in need of both healthcare and passage to France is perhaps the strongest force in the film outside of Keener. An apparent doppelgänger of a woman Lee photographer in Libya, Hafsia represents a connection to the past Lee is trying to escape and a way to remedy that past. The pivotal moments of War Story rely on the relationship between Lee and Hafsia and although they don’t quite deliver, still comprise a more valuable 90 minutes spent than half the movies hitting theaters this summer.