“An American near Billy wailed that he had excreted everything but his brains. Moments later he said, ‘There they go, there they go.’ He meant his brains.

That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.”

—Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

I open with this Vonnegut quote to assert that not all toilet humor is inherently bad. There is a tendency to associate gross-out humor with youth and children, who notoriously lack good taste. And crude humor is easy fodder for shock value, sometimes exploited as an easy way to market an otherwise meritless work of art. But this quote demonstrates — although admittedly, removed from its context, in a more withered and watered down way — humor’s ability to communicate the imperfectness of humanity. It also serves as a sobering reminder that this novel about aliens and time travel is also about the very real firebombing of Dresden. So while some consider toilet humor to be nothing more than throwaway poop jokes (and the genre has plenty of those), we should acknowledge that there are instances in which it is capable of reminding us of our own struggles with this disgusting mortality.

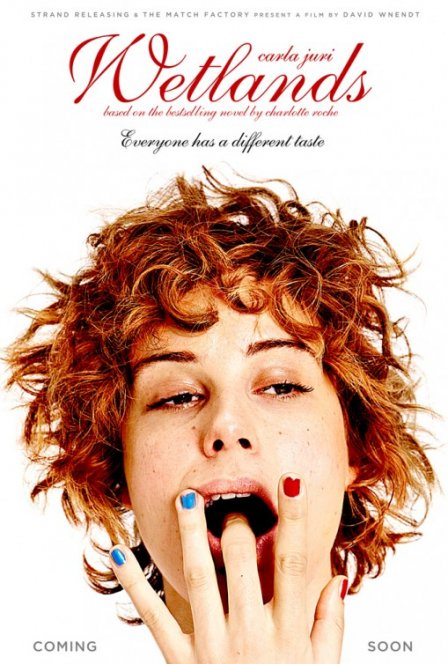

Which brings me to Wetlands, a German gross-out film based on a German gross-out novel about — most simply — a teenage girl and her hemorrhoids. The film employs a series of gross-out gags — and while some of them merely disgust, others strive to reach that upper echelon of transcendent relatability.

Helen (played by Carla Juri) is an 18-year-old whose fixation on her own genitals (“wetlands”) and bodily fluids is matched only by her disdain for — and neglect of — personal hygiene. When the unfortunate combination of hemorrhoids and an anal fissure land her in the hospital and she undergoes rectal surgery, she sees it as an opportunity to get her divorced parents back together. Along the way, flashbacks and fantasies explore her sexual urges and her relationship with her parents. It is never made explicitly clear how much of Helen’s persona is typical teenage rebellion, how much is psychological construct, and how much is something else entirely.

This ambiguity is part of what makes Wetlands so successful. But most of the success is owed to Carla Juri, who somehow manages to make Helen a charming character, despite her semen-stained hands, crass stories, and deviant nature. The fact that she is conspiring for the naïve cause of reuniting her divorced parents makes her more sympathetic (and her naïvety makes her more endearing).

Where the film comes up short is with its confused development of the romance between Helen and her male nurse Robin (Christoph Letkowski) — the other reason that Helen conspires to lengthen her hospital stay. Robin is a seemingly normal guy who is equal parts captivated and disgusted by Helen, drawn to her beguiling personality and aloofness. But he never becomes a full on co-conspirator, instead remaining unsure and apprehensive about her. While the film resists the urge to make Robin the male equivalent of Helen’s crudeness, it is never clear what it is about him that Helen is attracted to. This — combined with a revealing scene near the end that tries to over explain all of Helen’s eccentricities — mire the last third of the film in heavy-handedness and trite romanticism.

But despite this unevenness (and some largely uninspired direction from Wnendt), Wetlands is still a lot of wince-inducing fun. Full of spit, mucus, and shit, everyone is bound to find at least one scene that makes them squirm or ruins their appetite. Uniting the uncomfortable body horror of Cronenberg with the lowbrow gags of the American Pie series, Wetlands is not content to merely air dirty laundry. It wants to rub our faces in the soiled underwear, too.