All art is sacrifice. Whether it’s the psycho-spiritual toll of a tormented spirit, the impoverished struggle of the bohemian, or the pop cultural quasi-science of Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours, there is an embedded notion throughout history that artists must relinquish a part of the human experience to produce the works that we remember today. Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash provides a self-conscious take on the idea of artistic self-sacrifice, referring throughout the film to the story of Charlie Parker dodging a chair thrown by an irritated band leader whose name is now much less regarded than the legendary jazz saxophonist. Without that chair, per the logic of the film, Parker would just have been another session musician; under the threat of physical harm and utter humiliation, Parker acquired the dedication to become one of the all-time greats in jazz history, the guy we remember with the single moniker of Bird.

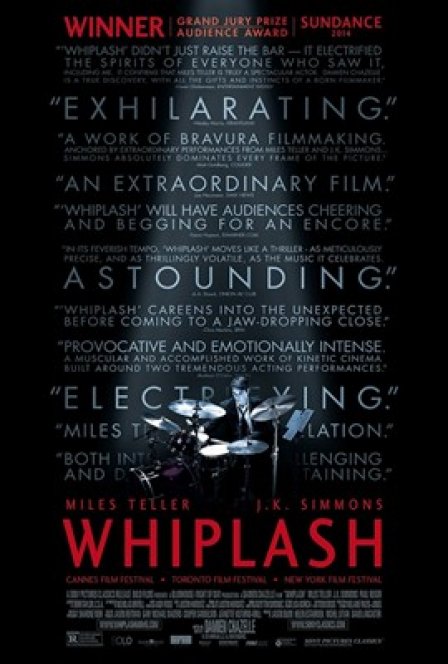

In Chazelle’s take on this story, the aspiring Charlie Parker is Andrew (Miles Teller), a young jazz drummer, and his chair throwing band leader is Fletcher (J.K. Simmons). The film tries to convey the emotional upheaval of Andrew’s quest to become the next Buddy Rich — Chazelle ensures the audience knows this is Andrew’s specific goal by having him look at a picture of Rich on his wall as he practices, then immediately cut to him playing one of Rich’s albums — but it is really the physical, bodily aspects of jazz percussion that seem to interest Chazelle. There are extreme close shots of Andrew and other drummers sweating profusely at the drum set. Andrew’s hands literally bleed from overuse at the dictatorial mandate of Fletcher’s rhythm. In practice montages, Andrew ices down his hands the way a boxer might after a long sparring workout. From a thematic standpoint, Chazelle, a Harvard graduate, must feel as though he’s invoking Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain.

Cinematically, however, Chazelle is simply reworking a movie that’s nominally about aesthetics by using the tropes of the sports film genre. Rather than being an emotionally manipulative failed artist taking out his own demons on aspiring students, Fletcher is essentially a screaming football coach, launching profanity-laced tirades at his players when they fail to live up to his arbitrary standards. Like the tyrannical coaches of sports filmdom, Fletcher rests on his ensemble’s records at competition, or in more familiar lingo, the trophy case. Chazelle seems to understand that abusive relationships rest on the Jekyll and Hyde element of the abuser, yet apart from two scenes in which Fletcher softens up to the point of being human, he spends most of the film shouting homophobic slurs. Andrew, on the other hand, is the second stringer who gets promoted to the starting lineup who then finds he must give up his personal life to focus on keeping his position on the team. There are practice montages galore. Apart from the effective lighting of indoor scenes and the soundtrack, this could be a movie about any competitive activity.

Perhaps this effect is merely a byproduct of the institutionalization of an artistic form like jazz music, but Chazelle does not hint at or explore this idea. Indeed, jazz seems to be a somewhat arbitrary choice, especially for a character with Andrew’s stated ambitions. While he continually references Charlie Parker as an idol, there is no real mention of the fact that jazz has not produced a culturally relevant figure in at least a generation (Parker died in 1955). There is an underlying absurdity at play here that Chazelle seems unwilling to acknowledge. For instance, the sequence in which Andrew’s car crashes into a truck as he races to the main jazz competition, forcing him to hobble bloodied and crippled into the main competition, could easily play for camp, yet the film presents it with a straight face. Later, Andrew, recovering from his “drum” addiction, takes a walk outside past some street drummers — drums are everywhere, man — but the film presents this as an honest psychological dilemma rather than a mocking take on an artist whose self-absorption led to destruction. A looser, more playful approach could have made this film into something interesting, but Chazelle, like his protagonist, prefers to work within a systematized structure that provides the audience with a sense of familiarity rather than wonder.