Similar to how the first 50-plus years of cinema reveals the prominence of literature in the collective psyche — countless novels turned into feature films, Hollywood scrambling to hire the nation’s best authors to write screenplays (with mixed results) — contemporary cinema shows how the cinema itself has become its own inspiration for narrative revamping. In the last decade, we have seen Hollywood turn to its own work as source material, with no signs of slowing. Film after film is remade for the modern era, our own hopeless quest to renew the past and make it our own. Which isn’t a bad thing: films, like all forms of art, have always been created based on other material, and the shift to making films based on films is not all that different content-wise from films based on novels and short stories.

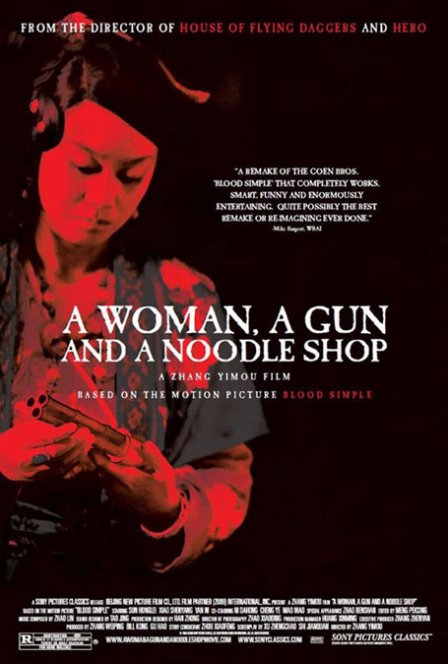

Yet, creating a film based on another film comes with baggage, the most obvious of which is the inevitable, tiring comparisons to the original. We don’t even really expect greatness from these films. No one thought, when they heard about the Karate Kid remake, Look out Battleship Potemkin. Surely all of this occurred to director Zhang Yimou as the idea of remaking the Coen brothers’ debut Blood Simple took hold. But Zhang, despite his penchant for flowery stylization and action-packed melodrama, comes through in recreating the Coen sensibility while making A Woman, A Gun and a Noodle Shop decidedly his own.

Zhang’s film is faithful to Blood Simple in style and story, though shifting the story’s location from a Texas bar to the Chinese noodle shop in the countryside. Yan Ni stars as the wife of shop owner Wang (Ni Dahong), an abusive and sinister man who suspects her of committing infidelity with fellow co-worker Li (Xiao Shenyang). It’s all set in the bright colors and touches of ornate set-making that you’d expect from Zhang, except the vistas here are sun-bleached deserts devoid of life, a Coen standard. Shenyang acts as a modern Buster Keaton, adding a touch of physical comedy to a film that shows hints of darkness when a gypsy sells a gun to Wang’s wife, a sort of Eve in the downward spiral that is to come. Her intention: to kill Wang.

The story continues to unravel as it barrels towards the inevitable. Here, Zhang allows for the kind of ambiguity that the Coens relish, with the same nonchalant grace that makes the brothers so exciting. Each character becomes increasingly paranoid, making ludicrous decisions to assure their control in this situation where the actions of the characters are unpredictable to all involved: the policeman who reports the infidelity to Wang is out to take him for all he’s worth; Wang’s wife wants to kill him; Li wants to run away with money; the other two employees of the noodle shop want to take the back-pay Wang owes them; and no one is even sure how many players are involved in these interwoven plots against Wang.

Yet despite any seriousness in the narrative, A Woman, A Gun and a Noodle Shop leans heavily on the comedy end, to the point of frequently being slapstick. Makes sense too: Blood Simple is really a comedy of errors, an account of the fruitless drive for power that informs most human interaction. It’s anchored by inevitability; the drive to power only leads to self-destruction. Its ultimate message: There is no such thing as control. At times, the bright colors and the comedy feel nearly sacrilegious to anyone with a reverence for Blood Simple, but there is a subtlety displayed here that films like Hero or Curse of the Golden Flower don’t trade in. And by the time the whirlpool of error has begun spinning fast enough as to blur all intentions, it’s impossible to deny that these are the things that make this film particularly Zhang’s, not just another remake of a better film.