Paul Baran’s Panoptic is grounded on a concept, and so we get to play the sometimes impossible and oftentimes frustrating game of matching up the sounds with the ideas that motivated the artist. As exasperating as this might be, it’s certainly stimulating to be invited to the discussion by an artist who, having ruptured the stale and passive relationship many have with the sounds they consume, thinks that the listener has an active role to play as the one who discovers the elusive connection between concept and sound.

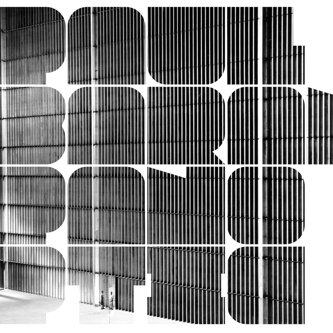

Baran — joined by Keith Rowe, Werner Dafeldecker, Armin Sturm, Rhodri Davies, Sarah Whiteside, Andrea Belfi, Gordon Kenney, Davy Scott, and Timothy Cooper — conceptualizes Panoptic as “an attempt to soundtrack the lives of creative people affected by such concepts as underclass, surveillance and the dangers of mass consensus.” The title takes its name from Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, a prison designed such that the prisoners are always being watched but never know with certainty that they are. The sounds have an uncomfortable feeling flowing throughout them, some sort of suspicious, tingling presence, patiently brooding but waiting to rupture.

The fear of perpetual surveillance, though, doesn’t quite capture the eeriness and paranoia of Panoptic’s minimal drones, whirrs, and clicks of mysterious ambient sound. The true terror comes when one realizes that the external gaze of authority has been internalized, and that one is self-policed. We can imagine city streets while absorbing these sounds — desolate places where few bodies move due to the overwhelming mistrust of the always cloaked gaze — but we can also understand these sounds as being internal bodily and thought processes: imagine something that is never uttered aloud, but through whose suppression it becomes an instance of psychological torment.

The internal and external world Panopticportrays is not the Dionysian orgy of unhindered creative ecstasy. The bodies in this world are not free, but are governed by a multitude of invisible and unconscious forces: the static washes over random digital beeps of ultimate alienation and loneliness; piano phrases that drift timidly; the hum of an acoustic guitar; metallic objects screeching in the distance like the swings of some abandoned, lifeless playground. Most engaging is Baran’s understanding of space on this recording. Sounds enter the ear from unpredictable places — lurking, approaching, and disappearing — showing that Baran has created an entire world of shifting, dislocated, and, perhaps puzzlingly warm atmospherics. Despite this album’s tendency to make the hairs stand up on the listener’s neck, it is undeniably welcoming. While paranoia and alienation seem to be the most pronounced moods motivating this album, it is not itself lifeless. The objects are allowed to speak for themselves, and there is certainly some beauty — not just visually, but also aurally — about empty spaces where humans once walked but have now fled.

Toward the end of the album, beginning with “Brauzenkeit (Ekkehard Ehlers Mix),” a new, more disruptive presence emerges; the rumbles and glitches become more confident, as if they’re preparing to shrug off their restraints. On “PIN-Snipers,” one gets the impression that there is some detrimental glitch in the machines — that they aren’t quite working as well as they should be. The rupture finally occurs with “To Protest In Their Silence,” which is the most violent sound-moment of the composition. A mechanical fire bursts forth and the static pulses turn on one another antagonistically, an event that allows us to see the weaknesses within the watchful structures of domination. It is this rupturing moment that is the most important, for it suggests the possibility that these power structures, and the forms of life they perpetuate, are necessarily dependent upon us, and not vice-versa. It is by capturing this real possibility that makes Panoptic such a dynamic and critical sound-experience.

More about: Paul Baran