I’ve always felt a little uneasy about Bruce Springsteen. There just seemed to be too much work getting in the way of his music. There’s the whole New Jersey thing, and all that blue-collar romanticism, and the trading-card personalities of his band, and the mythic characters in his songs, and the four-hour long concerts, and the massive box sets, and the blinding star power of Springsteen himself. I’m not necessarily opposed to mixing any of those things with music, but it all seemed so exhausting, so demanding, especially if you’re looking for a more immediate kind of release, some less tortured way of getting your rock ‘n’ roll kicks.

In a way, though, my resistance was mostly generational and, sure, economic. When it comes to taste, timing is everything, and I was born just a little too late to appreciate Springsteen’s particular kind of magic. By the time I started working my own shit jobs in Queens, NY, Springsteen had already established himself as a staple of FM radio, a classic rock god with a massive working class fan base. While I was chucking pennysavers out of a station wagon, or hauling mufflers across a garage, or scraping ice out of a freezer, there was Springsteen on the radio, singing his guts out about failed dreams and lost chances. I could acknowledge his talent, but I simply refused to let his music become the soundtrack to my life. I didn’t want to end up like someone in one of his songs; hell, I didn’t even want to end up like someone who listened to his songs. So I was drawn to any music that seemed to suggest a way out — the clean, new sounds of New Order and The Smiths, the edgy political rock of The Clash and U2, the cutting irony of David Byrne and Elvis Costello. But, still, everywhere, I was hounded by the more local sounds of Bruce and the E Street Band — sweaty, panting, hopeless — like some inevitable working class doom.

The Promise, a new collection of old songs cut from the Darkness on the Edge of Town sessions, doesn’t entirely dispel these feelings, but it certainly suggests another way of accessing his music. Springsteen’s career can be defined as a struggle between two creative urges: one, a desire to recreate the simple joys of 1960s radio pop; and two, a deep commitment to make rock ‘n’ roll that changes the world. The Promise contains all the pop fluff he cut out of Darkness. There’s a gorgeous Holly takeoff (“Outside Looking In”), a killer Orbison tearjerker (“The Brokenhearted”), a Brill Building humdinger (“Ain’t Good Enough For You”), and a set of Stax soul beauties (“It’s a Shame” and “Talk to Me”) that will have you shaking in your best blue jeans. There’s also Springsteen’s own thrilling cuts of “Because the Night” and “Fire,” two sure-fire hits that he (incredibly) handed over to other artists. Consider it a pop exorcism: Springsteen wanted to create a mature album about “deep despair and resilience,” and all these teenage ditties about cars and girls suggested something false in his art, an immaturity of vision that got in the way of rock ‘n’ roll authenticity. In the end, Darkness became his “‘samurai record,’ stripped to the frame and ready to rumble,” while all these dippy love songs wound up in the dustbin of history.

Listening to these discarded songs, though, one begins to sense that this is a false dichotomy. On both Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town, Springsteen constructed epic narratives of failure and fate out of bits and pieces of classic pop. Even his most “serious” songs show traces of his guilty pop pleasures: the throbbing urgency of “Darkness on the Edge of Town” rests on its delicious Motown beat; the grown-up pathos of “Racing in the Streets” is nothing without the lyrical echo of Martha and the Vandella’s giddy pop fling, “Dancing in the Streets.” In fact, the songs on Promise seem like the songs that the characters in the songs on Darkness grew up on. This is the pop jukebox visited by the likes of Candy and Sonny and Terry and Johnny and Billy, the dream machine in the local bar against which their lives are defined as successes or failures. But it’s difficult to tell which album — Promise or Darkness — is the dream and which is the reality, which is the fantasy and which is the truth. While Springsteen wants you to think he stripped away all the falseness of pop in order to get at something real, the reverse is also probable: he buried the real pleasures of pop in order to construct the seriousness of rock. In a way, all the illicit thrills and kicks of the former were restrained and reworked into a presumably more “responsible,” but no more “realistic,” vision of adult life.

In the documentary that accompanies the box set release of The Promise, Little Steven takes his Boss to task for refusing to release the poppier stuff: “It’s a bit tragic in a way, because he would have been one of the great pop songwriters of all time.” Springsteen, in turn, tries to defend himself, but he winds up blurring his own distinction: “I think part of what pop promised and rock promised was the never-ending now, you know, the always, ‘no, no, no, it’s about living now. Right now you need to be alive, right now.’” As Springsteen knows, even the most banal Top 40 hit is infused with a certain class-consciousness. This “now” always has something critical about it, a need or demand for something else, for some better life. So, listening to The Promise next to Darkness, especially those songs that appear in slightly different versions on both, the boundary between frivolity and seriousness starts to dissolve. A folk ballad about Elvis’ death (“Come On [Let’s Go Tonight]”) proves no more or less gripping when it becomes a straightforward working class ode (“Factory”). A tongue-in-cheek Motown number about trying to please your uptown girl (“It’s a Shame”) has just as much urgency as its existential rock version (“Prove It All Night”). Authenticity and commitment can take many forms, and these songs, even at their most simplistic, all insist on the now, now, now.

In the end, the artificial pop of The Promise makes it, as a whole, a more realistic album. The very cheapness of these songs makes them seem surprisingly fresh and urgent. Springsteen at his most derivative appears more human, more down-to-earth than when he’s trying to seem down-to-earth; he becomes a guy who loves a good pop tune, instead of a guy who writes epic rock music that changes the world. But even this distinction fails to make sense. Maybe some of Springsteen’s baggage got in the way of his best music (that’s what Little Steven would say), but the struggle of his career, specifically his frustrated search for the real thing, is precisely what produced one pop masterpiece after another. In the end, all his songs seem to contain some kind of promise, and, more often than not, whether you’re under the hood or behind the wheel, they deliver it.

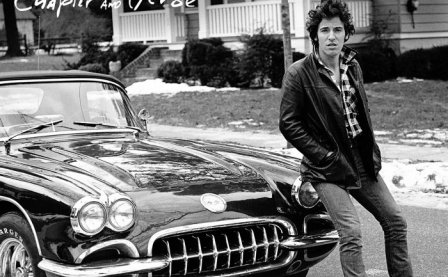

More about: Bruce Springsteen