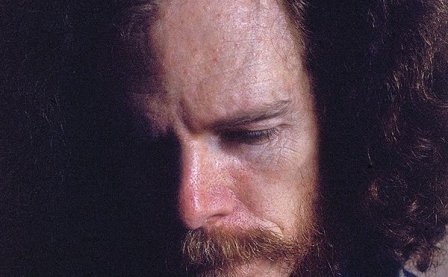

Singer-songwriter Ed Askew has in some ways been the epitome of the term “acid folk.” Bringing a white-hot, gritty quality appropriate for the yippie energy that permeated the American underground, his debut was released on ESP-Disk’ (Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, The Fugs) at the close of the 1960s. Instead of the customary six-string acoustic guitar, Askew played a Martin tiple, and the taut sound of the instrument’s strings coupled with the keening strain of his voice and opulently psychedelic lyrics made the self-titled album (reissued on CD as Ask the Unicorn) a cult classic of psych-folk. Then based in New Haven, Askew followed this auspicious session with Little Eyes (1972), which was slated for ESP but remained unissued until De Stijl rescued it in 2005. Askew went further underground in the 1970s, performing in coffee houses and on local access television, but it wasn’t until the mid-Aughts when he began to work with more regularity, self-releasing CD-R and cassette recordings made in his Washington Heights apartment and digging up archival gems for an excellent Drag City album titled Imperfiction. These days, he sticks to harmonica as vocal embellishment, while the tiple duties are handled by Tyler Evans, and pianist Jay Pluck rounds out Askew’s working band.

Released on the UK imprint Tin Angel, For the World is Askew’s latest ensemble recording and finds the core trio rounded out by harpist Mary Lattimore and bassist Cannan Faulkner on ten of the leader’s original tunes culled from recent years and decades past. Waxed in Harlem, the sessions also bring in a number of heavy friends, such as guitarist Marc Ribot and vocalists Sharon Van Etten, Eve Searls, and Jerry David DeCicca. It’s clear from the opening “Roadio Rose” that orchestration is a central focus for this music; whereas his previous outings were crackling and spare (whether fleshed out on tiple, guitar or piano), the addition of lush, cyclical piano; chunky harp flecks; and the simple flights of Evans’ electric guitar lend a sympathetic fullness to Askew’s haunting vibrato. Naturally, after nearly 45 years, his voice has become deeper and more fragile, but with that calmer and somewhat resigned energy comes an extraordinary nuance.

Askew’s songwriting is lyrically much simpler now — childlike innocence has replaced wide-eyed complexity, and the economy of his observations bring a huge-hearted spiritualism to the music. “Blue Eyed Baby” is just extraordinary, Askew and Searls marveling at a baby boy, a mountain landscape, and the open sea with matter-of-fact power. I can’t say I’ve heard much songwriting that is this sublime and yet so unadorned. “Gertrude Stein” is a reflection on Bohemia, biography, and the open-mindedness with which he encountered the world as a young man (and as an older gent). Accompanied only by tiple and electric bass, when Askew observes a young couple arguing and sings “I hope that they make up,” one can’t help but agree.

There’s a sprawl to this music that reflects age and easygoingness, and to a degree the songs don’t put their hooky cards on the table very easily. One could draw an interesting comparison, for example, between the version of “Roadio Rose” here and the 1971 take included on the CD issue of Little Eyes. That reflective quality surfaces lyrically as well, for Askew ruminates on others’ childhoods unfolding in rickety, glinting campfire ballads such as “So” (a battered upright piano clutching at the harp’s ankles) and its lengthier counterpart, the majestic trio chant “Drum Song.” That’s not to say that For the World is an entirely concentrated series of missives on what was, as the juiced-up present of the eternal wine-drunk now stamps itself out in the barrelhouse rondo of “Baby Come Home.”

Askew may have simplified his verbal structure and his delivery might be a bit burnished with age, but the quality of his imagery is as rich as ever, allowing one to extrapolate on hazy summer frolics (“Paper Horses”) and ephemeral architecture (the filmic and austere “Maple Street,” with an understated but incisive Marc Ribot). Of course, one always hopes that an underground hero’s latest album will bring the masses to the door, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that For the World should be in the collection of any fan of modern folk, chamber pop, and psychedelia. Sure, increased attention for the work both locally and abroad is a great thing, but whatever the outcome, Ed Askew will continue to write, observe, reflect, and create visions and words. This result is timeless enough to remain there if one wants it.

More about: Ed Askew