The word “mesmerize” is derived from Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer, an 18th-century physician who believed that animal magnetism could be reinforced and strengthened by sounds. Instruments, especially the glass armonica, figured notably in Mesmer’s experiments on human patients, many of whom would later report musical hallucinations. Decades later, neurologists at France’s Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital used tuning forks to induce supposed trances in their patients. This work led to Pavlov’s bell experiments, perhaps the most famous example of musical coercion. Throughout millennia, the purported ability of sounds to hypnotize has been conceived of with outright fear, as a direct threat to self-control, as a dangerous tool of seduction, and even as brainwashing during the Cold War.

But what if the subject wants to be hypnotized?

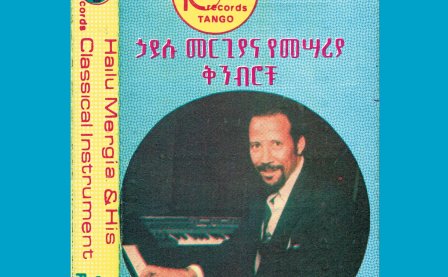

Lucky for us, many contemporary musicians embrace hypnotic effects in their music. Highlighting aberrant or alien tones is just one method of inducing trances. Ethiopian music systems, with their various five-note scales, or “kiñits,” act as alternatives to the Western standard and a method for inducing sonic reverie through their blissfully hypnotizing songs. In the history books, the Walias Band is one of the country’s most significant groups furthering what is now known alternately as “Ethio-groove” or “Ethio-jazz.” Among the luminaries in the band were Mulatu Astatke, who has enjoyed a renaissance through his inclusion in the soundtrack to Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers, and keyboardist Hailu Mergia, who has kept a lower profile over the years, continuing to operate a taxi in DC and practicing while not on duty with a AA battery-powered keyboard. Lala Belu is his first album of new material in 15 years.

Album opener “Tizita” references one of the Ethiopian scalar modes, directly giving newcomers a chance to get acquainted — and yes, hypnotized — by the undulating rhythms and twisting, sharp lead. But the 10-minute track has more in store, as it switches up not once, but twice, first revving from a relaxed groove to an uptempo, piano-driven section before finally multiplying into a free-for-all jam straight out of Chick Corea. “Addis Nat” and “Anchihoye Lene” both lay down grimy funks, drums punched up in the mix, the melody snaking around. The dreamy “Gum Gum” coaxes multiple swirling organ melodies across a swinging beat guaranteed to get your feet tapping, while the title track contains the only semblance of lyrics on the entire album, a chanting theme set against organs and meandering synths evoking the Ethiopian church that shares its name. Mergia strips all elements back to Pavlovian simplicity on the album closer, the solo piano “Yefikir Engurguro,” showing that music need not be complex to be transfixing.

Listening to Lala Belu brings to mind the Arabic concept “tarab,” which contains multiple meanings: “an emotional state aroused in listeners as a result of the dynamic interplay between the performer, the music, song lyrics, the audience, and…an ‘ecstatic-feedback model’ of the tarab culture,” according to cultural anthropologist Jonathan H. Shannon. This state of musical ecstasy from one of Ethiopia’s neighboring cultures may provide a better model for understanding how we surrender to sounds rather than relying on clinical analysis. With only six tracks, Lala Belu shows that being hypnotized is what we secretly want.

More about: Hailu Mergia