Thank you, Janelle Monáe. For weeks, I’ve been haunted by the image of Miley Cyrus pretending to rim the ass of one of her black dancers on the stage of the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards. Most of the press skipped over this overtly racial display to focus on the YOLO-shenanigans between Miley and Robin Thicke. Some of the smarter commentators, though, were less troubled by her sexuality than her white privilege, especially since such privilege was hiding in plain sight behind the fake politics of her post-tweener liberation. For me, however, it was really just that one lingual gesture, violent and obscene, reducing the dancer to her own black body and then, in its anality, even less. Miley’s full-bodied dancers served as nothing more than props — not just stage objects, but actual “property” — no better than the other zonked-out chocolate teddy bears there to be used for her own infantile oral pleasure, or, really, the visual pleasure of Big Daddy Thicke. No amount of irony or backhanded feminist theory could save this act, and I couldn’t imagine any form of high or low culture potent enough to blast it away.

And, yet, here I am, a mere two weeks later, with the super sweet chorus to Janelle Monáe’s “Electric Lady” on a constant loop in my head — a smooth sonic cleanse. I wake up singing it; I go to sleep singing it. It’s there in the shower, on the way to work, in the halls — “Electric lady! Get wayayayaya down!” Oh, man, that slicing hi-hat, the hand claps, the fat bass, the wonderful twin-jet melisma of Janelle and Solange — this is one black female neo-soul ballad that I could live in forever.

Miley sings this:

To my home girls here with the big butt

Shaking it like we at a strip club

Remember only God can judge ya

Forget the haters ‘cause somebody loves ya

And Janelle sings this:

Ooh, you shock it shake it baby

Electric lady you’re a star

Kinda classy kinda crazy

But you know just who you are oh!

On paper, they’re actually a lot closer than you think. Both women are tapping a freaky politics of psycho-sexual liberation, using age-old primitivist notions of black embodiment to reconfigure the terms of female body politics. In fact, they’re both advancing this logic in a bid for wider mainstream success, competing in a cramped commercial market that consistently mines the cultural politics of the past for new product (it kills me that I first had to go to VH1’s website — which is plastered with pics of Miley — to hear Janelle’s album). In fact, while mostly known as an aloof and cerebral performer, Janelle has stamped the liner notes to The Electric Lady with a bright red sketch of a woman’s booty — both ancient hieroglyph and modern sexual fetish. But whereas Miley’s music is neurotically shaped by the male gaze, the logic of property, and the narcissism of possession; Janelle’s music is sisterly, self-assured, and utterly triumphant. Whereas Miley’s voice is both anxious and exhausted, giving off a broke-ass Vodka Sam vibe, Janelle’s is brimming with personal agency and generational energy, tapping a rich female soul tradition — her album is lifted by the spirits of Ross, Flack, Bassey, and Jones, to name just a few — to project a bright and viable future.

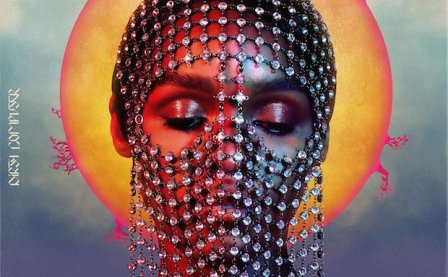

Enough, though. There’s only one party I want to be at this year. Janelle Monáe’s The Electric Lady is simply wonderful. As the latest installment in the cyber-soul adventures of hot-bot Cindi Mayweather, it’s a time-tripping, genre-hopping electro-booty fest of R&B history — doo-wop, funk, disco, reggae, psychedelia, and 80s synth-pop — all in the service of black feminism, queer sexual politics, and futuristic android Other love. In both sound and concept, it’s a complete freak-out: cheeky exotica suites alternate with fake radio broadcasts from WDRD (a droid-friendly radio station), while Janelle, as Mayweather, moonwalks from one genre to the next like some funky-footed Dr. Who. If Mayweather seems distracted here by an illicit romance that just may or may not prove the key to her mission, the concept allows Janelle to explore the multiple varieties of soul — and its shifting sexual politics — as they provide alternative ways of being black and being beautiful. In fact, The Electric Lady is more romantic and more sexual than anything we’ve heard from Janelle in the past, but the turn serves her Afro-futurist agenda well. Here, she does George Clinton one better, pushing his freaky sexual politics — “All that is good is nasty!” — toward its breaking point, taking command of the Mothership and resetting its course for a more genuinely open future. As she sings on “Electric Lady,” backed by the funkiest rhythm section since the days of the Funkupus,

Yeah I’ll reprogram your mind come on get in

My spaceship leaves at ten

Oh, I’m where I want to be just you and me

Baby, talking on the side as the world spins around

Then you feel your spine unwind

And watch the water turn to wine

Ooh! shock it one good time

But while Dr. Funkenstein and Ziggy Stardust seem the most obvious intergalactic precursors to Janelle’s Mayweather, one also detects here the influence of Quentin Tarantino’s Django. The Electric Lady shares Tarantino’s obsession with the Spaghetti Western soundtracks of the 1960s and the disco soul of the Blaxploitation era, and Mayweather’s genre-scrambling journey to the past, much like Django’s, serves to repair racial history according to explosive contemporary protocols. Janelle’s high-concept cyber-noir script is no distracting sideline to the music, but the very best stuff of sci-fi genre-bending and reparative historicism. In the context of the album and its retrospective soul-scape, the first single, “Dance Apocalyptic,” with its girl-group bubblegum bop and queer subtext, comes across as no less thrilling than the burning of Daddy Candie’s Great House. “Smash! Smash! Bang! Bang! Don’t stop! Chalanga langa lang […] It’s over like a comic book/ Exploding in a bathroom stall.”

As Janelle’s alter-ego, android Cindi Mayweather (Burkheart Industries, Alpha Platinum 9000, #57821) provides the key to appreciating the shifting styles and thematic preoccupations of her music. Like Dr. Funkenstein, the voodoo priest/mad scientist who exploited the modern recording apparatus to set his army of clones into funky motion, Mayweather also works the incredible plasticity of pop musical being. A futuristic funk machine, one archived and programmed to cross-fade from rap to reggae to sultry soul, she embodies all the ways in which sound and rhythm can remake human identity. Working the rift between body and voice, or even vision and sound, nature and second nature, she is an avatar of sheer sonic becoming — less prosthetic godhead than universal super-DJ working the dance floor of history. On The Electric Lady, Janelle wonders whether she should “reprogram, deprogram, or get down,” but her acoustic android power is most clearly on display when she switches genres on a dime, freeing up her sound and the history to which it refers. “Q.U.E.E.N” starts off as a freak-funk blowout; behind squonking synths and voodoo beats, Janelle counts all the way of being freaky — “We eat wings and throw them bones on the ground” — and finds she likes them all. But, as Erykah Badu coos, in an amazingly tight guest spot, if this “freedom song” is too strong, then we “movin’ on.” And, then, Janelle, taking the cue, says, “yeah, let’s flip it. I don’t think they understand what I’m trying to say,” and launches into her own fierce rap, boasting, “I’m tired of Marvin asking me, ‘What’s Going On’?/ March to the streets ‘cuz I’m willin’ and I’m able/ Categorize me, I defy every label.” As musician and performer, Janelle is often less expressive than gestural, using — in both sound and look — the archive of the past to stage urgent interventions in the present. Like Elvis before her, or, better, the shape-shifting Michael Jackson of ThrillerThe Electric Lady, she exploits the open codes of the pop market to her own advantage, disappearing in the process only to emerge again and again as its queen: “She can fly you straight to the moon or to the ghettos,” she sings on “Electric Lady,” “Wearing tennis shoes or in flats or in stilettos/ Illuminating all that she touches eye on the sparrow/ A modern day Joan of Arc or Mia Farrow/ Classy, Sassy, put you in a razzle-dazzy/ Her magnetic energy will have you coming home like Lassie.”

But that’s just the start of it. Janelle’s android status is vexed, liminal, other. She comes from the future in order to save the past, but while her advanced knowledge includes the universality of love, her ambiguous status marks her as monstrous and fugitive. As Janelle explains in a recent interview with Elle, “I grew up in Kansas City, Kansas, and grew up in the language of the oppressed and the oppressor. I just felt that it was time to talk about that. […] The android is just another way of speaking about the new other, and I consider myself to be part of the other just by being a woman and being black.” The Electric Lady offers up the droid wars, academically, as a metaphor for race war and gender war. Most of the backstory comes in the form of radio programming from WDRD, as listeners call in to express their droid love or, alternately, to voice disgust — “She’s not even a person!” “Robot love is queer!” The album’s political ambitions, however, are more powerfully conveyed when Janelle lets go of the myth and focuses on her own life and experiences. “Ghetto Woman” taps the best of 1970s tropical disco to track the plight of the working black woman. Dedicated to Janelle’s mother, who worked as a janitor to put her daughter through school, the song uses its urgent musical form and soaring vocals — with Judy Garland and Diana Ross as its sister muses — to project a compelling elsewhere to the “ghetto land.” In other moments, The Electric Lady explores the re-humanizing solace of love and dwells on a future in which the human — or the human/other binary — ceases to exist at all. Tracks like “Givin Em What They Love” and “Sally Ride” tap the moonscape psychedelia of early Pink Floyd and the spacey orchestral rock of Elton John to project a weird, post-human elsewhere. On “Sally Ride,” an homage to another fallen space-woman, Janelle, as Mayweather, sings defiantly, coldly of abandoning her mission: “I’m packing my space suit/ And I’m taking my shit and moving to the moon/ Where there’re no rules.” You just can’t help rooting here for Mayweather and Mary (friend? lover? fellow android?) as they project a new start in this brave/queer new world.

Ultimately, it is this coldness, this bright chrome armor that defines both the android figure and its possibilities for Janelle. The android is strongest in its androgyny, its blankness, its objectivity; Janelle wears her technology like a queen’s crown, and she’s using it here — track by track — to get her pyramids back. Once again, we find her dwelling on the revolutionary possibilities of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and its key line: “There can be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator.” At her nastiest best, though, Janelle sheds her humanist skin — comes on as Robot Maria, not Human Maria — transcendent consciousness, all brain, hands at the boards, little heart. “I am sharper than a razor,” she croons on the album’s opener, backed by Prince’s vicious guitar vamp, “Eyes made of lasers/ Bolder than the truth […] I ain’t never been afraid to die/ Look a man in the eye.” Janelle’s android status grants her not just strength, but clarity, a vision unclouded by the hazy ideologies of the past and present. It’s an armor that cuts through the fantasies of female blackness, a refusal to put forth her own body on any terms than her own. Ultimately, by embracing this cold inhumanity, she becomes again a human subject and not an object of history, blazing cool footholds through time. In a series of jazzy exotica experiments at the end of the album — “Look into My Eyes” and “Dorothy Dandridge Eyes,” for example — Janelle turns the colonizing gaze back around, commanding attention and power with her own vision. Elsewhere — as on “PrimeTime,” a deceptively simple lose duet with Miguel — she outlines the terms of a progressive romance, one defined not by possession, but by agency and consent; “Is that okay?” the lovers ask, as the stars blaze around them and the violins glide. And then when she needs it, Janelle will let her android style conceal as much as it reveals. This armor not only protects, but also hides. A grand refusal — to perform, display, expose — marks Janelle’s best, fiercest work; her style as much blinds as it expresses, and ultimately there are rooms at the back of this booty party that no man will ever enter. In a verse from “Givin Em What They Love,” one that was ultimately left out of the album’s liner notes, Janelle croons,

Two dimes walked up in the building

Tall and concealing, wearing fancy things

Chopped up with a knife, hammered like a screw.

When they walked in the room we didn’t know what to do

One looked at me and I looked back

She said, “Can you tell me where the party’s at?”

She followed me back to the lobby

Yeah, she was looking at me for some undercover love.

Too long, too indulgent, too egotistical, too many styles, too many embellishments — while critics tend to depict Janelle as a robotic control freak, they just as frequently accuse her of lacking restraint. Girl can’t catch a break. But The Electric Lady is meticulously loose and programmatically sloppy — both hygienic and nasty. Sure, the album’s “Gender Studies 101” pop academicism sanctions some dodgy connections. Just as Janelle trips from ska to synth-pop, she perhaps all too easily blurs the lines between “android” and “negroid” as well as “Q.U.E.E.N.” and “Q.U.E.E.R.” But Janelle spins High Theory just as loosely as Low Funk — it’s all part of the apocalyptic party mix. By overburdening her album with concepts and styles, she actually achieves the opposite, freeing it all up as a space of end-times play. Even the very obvious bid for mainstream success that marks songs like “PrimeTime,” “Can’t Live Without Your Love,” and the lovely “Victory” comes across here as part of the “mystical battle plan.” Janelle gathers all of it — the concepts, the genres, the images, the marketing — under her bright-eyed love of pop’s sloppy democracy, where you can’t tell the difference between chicken and pork, between robots and the real kids, but where the booty never, ever lies. On WDRD, a pair of droids introduce “Dance Apocalyptic” as Mayweather’s “newest jam,” but it’s actually a very old one — a doo-wop chipmunk bop reminiscent of countless other end-of-world stomps: “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Suffragette City,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” etc. etc. It’s a fitting end, but also apparently just the beginning of the party. “Female Alpha Platinums are in for free. Clones and humans welcome after midnight […] No bounty hunters allowed.” Mayweather’s ready to take the stage. Janelle just wants to know which side you’re on. “If the world says it’s time to go,” she asks on the refrain, “Tell me will you break out?”

More about: Janelle Monae