Judging from the pages upon pages already written about Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, you might think that critics have already exhausted the conversation within just the first week after its surprise release. Some valuable interpretations have surfaced, and the exuberant praise that some have lavished on the album is due. But so many reviews have heaped up recycled platitudes about the album’s somehow-surprising blackness, its supposedly-inscrutable complexity, and its take on the suddenly-topical string of police murders that have recently gained mainstream awareness (but have been going on for decades) that a complete reading of the album’s lyrical content hasn’t yet breached the press. It’s not necessarily unexpected: on the one hand, critics are responsible for doling out only the fairest share of hype, leaving the fawning and the hating to the fans; and on the other, they have mere hours to determine the value of the work and form a coherent statement about it. Writers struggle to say anything conclusive, and when they do, it’s often so myopic that it seems to miss the point entirely, taking the music at face value.

To Pimp a Butterfly requires an extra commitment. Even the most casual attention to the lyrics can unveil the complexity of Lamar’s critique of institutional racism, consumer capitalism, hip-hop culture, justice, and his own choices as an artist, as a black man, and as a human being. Although some critics have recognized that Lamar’s myriads of vocal personae and lyrical points-of-view allow him to approach these issues from multiple angles (resulting, for some, in disorganization and fragmentation), few have sought to capture the weight of the album’s seemingly paradoxical investigations of its major questions.

What follows is an attempt to read the album’s underlying narrative, a story that unites all the layers of the album’s critique into a coherent whole. To Pimp a Butterfly provides nothing less than a dialectical account of the relationship between the constantly-emerging revolutionary consciousness of black culture and the bare materialism and institutionalization that threaten to destroy it. In doing so, the album organizes itself around three major poles: money, power, and the self, the vessel of consciousness. When we finally arrive at the ghostly interview with 2Pac at the album’s close, Pac describes this fully-realized awareness as spirit.

Caterpillar in the Money Trees

Money plays a complicated role on To Pimp a Butterfly. Perhaps the most prominent theme of mainstream rap since back in the day, money reveals itself here as a means not only for survival and luxury, but also of oppression and injustice. Back in 2012, one of Lamar’s lyrical personae said he felt like “money trees is the perfect place for shade.” But from the beginning of “Wesley’s Theory,” it’s clear that the struggle continues even when the money flows freely. Dr. Dre phones in: “Remember, anybody can get it. The hard part is keeping it, motherfucker” (all lyrics sourced from Genius’s labor of love, staggeringly complete since the day of the release). The titular reference is to Wesley Snipes, convicted of tax fraud for filing massive, fraudulent tax returns based on loose interpretations of the tax code. In short, Snipes tried to cut off his own flow of cash to the US Government as a form of protest, starving Uncle Sam of his lifeblood. That’s the basis of Lamar’s argument against consumption on the track and a presage of the danger of protest later explored on the album’s final cut, “Mortal Man.” But the persona Lamar adopts here is not yet anti-materialistic, and he hasn’t yet left behind the hypnotic magic that material things work on consciousness. Here, it’s the act of consumption itself, and the debt required to do so, that meets Lamar’s critique, and he shows how it plays directly into the wars being fought in and out of the hood. Consumption funds, via tax revenue, the same justice system that will “Wesley Snipe your ass before 35,” killing you or imprisoning you before you reach the minimum age to become a US president. Check the interlude on “Institutionalized”: “If I was the president, I’d pay my momma’s rent.”

Lamar repeatedly plays on the false promise of slavery reparations in the form of “40 acres and a mule” by putting it in the mouth of his Uncle Sam persona as a material offer that is now finally available to Lamar due to his cash flow. Likewise, Sam lets him know that “motherfucker, you can live at the mall,” offering the very site of hyper-consumption as a consumable quantity. This cavalcade of consumption finds its metaphor in Lamar’s organizing myth of the caterpillar and the butterfly, loosely based around Eric Carle’s classic children’s book The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The caterpillar consumes everything around him seemingly in order to protect himself. Recognizing his nascent talent (and nascent consciousness) as a valuable resource, the caterpillar “pimp[s] it to his own benefits” (the story doesn’t deal so much with being pimped by others, as Noisey’s Ryan Bassil suggests, but rather in pimping yourself).

This follows with the album’s next moment of money consciousness, “For Free?” Conceived as a black entertainer’s reply to a barrage of insults from America about his inability to pay for material things, Lamar dances over a bop-era jazz beat, asserting: “Oh America, you bad bitch/ I picked cotton that made you rich/ Now my dick ain’t free.” With this persona, Lamar asserts the self-actualization of the entertainer-businessman, but this self-assertion is still material in content: “I need 40 acres and a mule, not a 40 ounce and a pit bull.” It’s still just a matter of degrees, but those who think that this is a mere contradiction to the consciousness of latter tracks like “How Much a Dollar Cost” have missed the significance of the caterpillar myth, because Lamar’s persona is here stuck at an early stage in the progression, still in the mindset of pimping himself, though no price is yet set.

The hypnotic and lush (thanks to masterful production by Taz Arnold and frequent K.Dot collaborator Sounwave) but insidious “For Sale? (Interlude)” communicates the price of admission, marking a turning point in the material consciousness of the album. Lucy, short for Lucifer, here in the guise of a stupefyingly beautiful woman who makes all the right promises to the cartoonishly lovestruck Lamar, shows up playing, as always, a much deeper game. The wealth and power she offers is available, if only Lamar will sign the contract, deeding the butterfly, his soul, to the devil’s control. Here, we see three poles of the album’s consciousness aligning in a single, but inverted gesture: the exchange of money and power for the soul. This is less Faust and Robert Johnson and more Jesus in the desert, less sealed pact and more temptation. Although Lamar has clearly signed a contract for To Pimp a Butterfly, perhaps even violating his own sense of consciousness, we see in the poem “Another Nigga” — which is gradually unveiled throughout the album — that the evils of Lucy send him “running for answers/ until [he] came home” (He thanks rap for sending him back on the following track, “Momma”). Other moments of awareness follow: confronted with the poverty and death in his hometown of Compton, the same old mad city, Lamar realizes that he has failed to use his resources to help his community.

It all builds up to “How Much a Dollar Cost?,” the last step in this passage from hyper-consumption to freedom from the bonds of material greed. It’s a striking inversion of “For Sale?’s” temptation story. Here, a transient confronts the speaker asking for a single dollar (not his soul) and Lamar, in increasingly angry tones, repeatedly rejects him, letting him know that he needs all his “crumbs and pennies,” thinking he’s got the panhandler figured out. But it’s no surprise to us to find out that the “bum” is none other than Christ himself, and that Lamar’s denial of him amounts to a rejection of the messianic power of selflessness and brotherly love. No matter how “cornball” you think that is, charity and compassion are the Jesus’s M.O.; “For it is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” (Luke 18:25). Critics and fans who groan at Lamar’s earnest spirituality must at least recognize the authenticity of his approach to his religion, which here smacks less of morality and more of active love, less Pauline sexual politics and miracles, and more Gospel wisdom and revolutionary healing. “Your potential is bittersweet,” as the homeless man says, if you can’t recognize the spiritual bankruptcy of wealth and the need of those around you dying of thirst.

When on “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)” Lamar reminds us that “Loud, rich niggas got low money/ And loud, broke niggas got no money,” the awareness has come full circle. 2Pac’s response in the album’s outro that now he’s going to “make millions for us” is a step forward; the simple use of the plural pronoun us makes all the difference in differentiating greed from the kind of selfless love that might change this country. Money is still a tool of oppression, and the certainty of death and taxes is assured, but the album’s final arrival at selflessness, at using one’s means to build up communities, is one of the primary methods available for accelerating the arrival of consciousness within the power structures that confine us. Bringing those power structures into definition, including both those of institutions and those within individuals, is the next stage of this process, a necessary one before the revolutionary we can find its definition.

good kid’s Cocoon

Power expresses itself in walls. Its ability to confine is perhaps its greatest asset, and therefore it manifests walls in unexpected places. At first, Lamar’s persona seems to be on top of the world, holding all the yams on “King Kunta,” a funky soul cut about the power and influence the speaker has gained in his rise from slavery to kingship. This track signals a kind of triumph, but an incomplete one. Lamar has risen from the level of the slave protagonist of Roots to become the one holding all the yams, the material signal of power from Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (“The yam is the power that be/ You can smell it when I’m walking down the street”). As such, it presents itself as a more standard hip-hop ego track, dissing rappers who share bars as prisoners who share a bed, claiming he ought to run for mayor of Compton. And yet a subtle awareness inhabits the song, citing Bill Clinton’s abuses of power and Richard Pryor’s freebase-induced suicide attempt. The track ends with the first lines of the poem “Another Nigga,” a second organizing motif that Lamar builds throughout the album: “I remember you was conflicted/ Misusing your influence.”

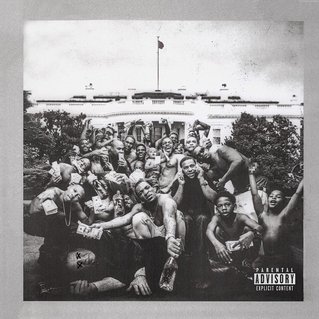

In Lamar’s caterpillar myth, the cocoon marks the institutionalization of the caterpillar stage. This phase is a bit slipperier, in that institutionalization is itself a complex of overlapping boundaries, both inner and outer. Here, the caterpillar is both imprisoned and pupating, caught in a hall of mirrors, locked in its own head but also in the power structure that the ghetto reinforces. On “Institutionalized,” the early interlude offers an image of the speaker in the White House getting high, freeing his homies and his mom from Compton, which is no doubt an image of material liberation, but not yet an image of consciousness and leadership. The White House is nothing more than a padded room for the fully institutionalized: “Be all you can be, true, but the problem is/ A dream’s only a dream if work don’t follow it.” Lamar’s grandmother echoes this sentiment on the hook, encouraging work both mental and material: “Shit don’t change until you get up and wash your ass, nigga.”

Lucy’s attempts to confine him send him physically running home for answers (he once said he was “tired of running”). The powers confining his consciousness here meet the tension of his own influence, and as he looks out on the mad city that made him, he witnesses the brutality exercised within his community as realized in the death of a dead friend’s little brother, knowing his absence has cost his home dearly. On “Momma,” a young kid from Lamar’s hood throws all of his knowledge into question: “Make a new list of everything you thought was progress/ And that was bullshit, I mean your life is full of turmoil.” The responsibility that this realization triggers shows up in expanded form on “Hood Politics,” which features Lamar’s strongest technical work on the album and the most classical of his vocal styles. “My lil homie Stunna Deuce ain’t never coming back, my nigga/ So you better go hard every time you jump on wax, my nigga,” Lamar asserts, swearing on his dead homies’ graves (those who passed away return on “Mortal Man” and the final interview with 2Pac, revealing that they’ve been speaking through Lamar all along). On “Hood Politics,” the whole system of the cocoon of power locks into place, revealing the landscape of institutionalization “from Compton to Congress” to the White House: “Ain’t nothin’ new but a flow of new Democrips and Rebloodlicans/ Red state versus a blue state, which one you governin’?/ They give us guns and drugs, call us thugs/ Make it they promise to fuck with you/ No condom they fuck with you/ Obama say, ‘What it do?’” Even music critics get their just deserts, called out for fucked-up priorities, “put[ting] energy in wrong shit.”

When “Hood Politics” ends, “Another Nigga” returns, and the speaker’s addition this time marks the new struggle he has entered: “While my loved ones was fighting/ A continuous war back in the city/ I was entering a new one.” Although Lamar could pull the trigger on a repetition of the East vs. West battles of the 90s (as Snoop did back in the day, according to some, at the 95 SOURCE awards), he’s understood that too much is at stake and instead seeks to be a leader against the cultural apartheid in the US, against the boundaries and confinement of the cocoon. “You wanna be like Nelson,” he states on “Mortal Man,” finally pushing this realization to its revolutionary crisis. The dark reality on this track is the same one every progressive leader and black star from Huey Newton to Michael Jackson has faced. It’s the last gasp of the cocoon, but it’s also the most dangerous, and it can run the gamut from cops planting drugs in your vehicle to straight-up assassination. Lamar asks, “If the shit hit the fan, is you still a fan?,” learning the lessons of history. The track ends by re-invoking the spirit of Mandela in a vow to lead the army of the righteous: “The ghost of Mandela, hope my flows they propel it/ Let my word be your earth and moon you consume every message/ As I lead this army, make room for mistakes and depression/ And if you riding with me, nigga, let me ask this question, nigga.” That room Lamar requests is the room the butterfly needs to spread its wings. This is K.Dot’s admission that the battle for true consciousness is never finished, that the mortal man who holds it is constantly struggling to keep it alive.

Black Boy Butterfly

As most critics have noted, Lamar’s internal struggle fills To Pimp a Butterfly, an unusual move for a hip-hop artist in that the foremost rappers typically exhibit only their sheer hardness and unflagging confidence. Critics have noted that 2Pac is exemplary in this confidence by contrast, somehow forgetting all of his suicidal thoughts (see “Only God Can Judge Me” or “Ambitionz az a Ridah,” on All Eyez on Me, for instance; or “So Many Tears” and “Death Around the Corner” from Me Against the World, the album that nearly shares a 20-year release birthday with To Pimp a Butterfly). 2Pac seemed to struggle too, in his own way, to realize consciousness, recognizing at once how trapped he was in the game and the necessity of carving out space for black power. It’s this awareness that Lamar attempts to synthesize, standing on Pac’s shoulders to see the future. But before he can arrive there, he has to rise above self-doubt and depression, which leads to his hotel-room breakdown as detailed on “u.”

“u,” no doubt the most bracing track on To Pimp a Butterfly, pits Lamar against his own reflection. The preceding outro of “These Walls” sets it up: “I remember you was conflicted/ Misusing your influence/ Sometimes I did the same/ Abusing my power full of resentment/ Resentment that turned into a deep depression/ Found myself screaming in a hotel room.” It’s not until the final track when we know that Lamar addresses “Another Nigga” to Shakur himself, but on “u,” we see the same suicidal thoughts he experienced exemplified in K.Dot, here as a drunken rant into the mirror: “Shoulda killed yo ass a long time ago/ You shoulda feeled that black revolver blast a long time ago/ And if those mirrors could talk, it would say ‘you gotta go.’” Crucially, what the speaker lacks here is self-love, resenting his own misuses of influence, because self-love has to contend with a paradoxical awareness of one’s past deeds, failures to act, and emotional weakness. As he says, “Loving you is complicated.” The self-consciousness that follows assertion, the reflection of the self on its own being, begins as self-negation, a failure to recognize that your own faults partake of the unity of consciousness. Doubt is the cocoon’s technique for holding consciousness within its walls, and it’s a particularly poisonous one, since it uses the caterpillar’s fear against itself and the nascent butterfly-consciousness, trying to snuff them both out before they can rise.

Although Pharrell lets us know that “we gonna be alright” on the hook of “Alright,” the combination of the narrator’s “u” and “i” as a we is not yet totally resolved. The negation on “u” generalizes into righteous anger on “The Blacker the Berry,” lashing out not just at the oppressor, but also at the we over and against it. The butterfly, now aware of the cocoon’s presence — the city’s walls, the race politics of the system, the violence within the community against itself — criticizes what he sees as the hypocrisy of the culture for perpetrating intra-racial violence on the one hand, and weeping for the murdered Trayvon Martin on the other. It’s crucial to read this track in light of the persona that Lamar adopts, and critics should be careful about interpolating Lamar’s statements about the Michael Brown tragedy into the lyrics here (especially if they fail to understand him). Ultimately, this track is about righteous pride and the assertion of black power against the oppressor, the flexing of wings against the cocoon’s physical form. As a white listener, Assassin’s hook on “The Blacker the Berry” brings it home to me too, binding the liberation of all races up with the liberation of the hood: “Every race starts from the block, remember that.” But Lamar’s on some tough love, because even if the prophet Marcus Garvey’s plans were to be realized, K.Dot reminds his listeners that the we still lacks unity (even though, as Rapsody states on her poetic verse from “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” “We all on the same team, blues and pirus, no colors ain’t a thing”). His lyrics imply that the inner work the butterfly represents is unrealized on a global scale.

When Lamar arrives home, he’s forced to question everything he’s ever known, as exemplified by the second verse on “Momma”: “I know what I know and I know it well/ Not to ever forget until I realized I didn’t know shit/ The day I came home.” But beyond the ego-dissolution of that stage, individuals still need to find personal peace before assuming the role of leadership. This moment finally occurs in Lamar’s “i,” the single so divisive for its positivity in the face of violence and oppression. What he realizes is basic but utterly crucial: “I love myself.” This isn’t Pharrell telling us over and over that he’s “Happy,” though Lamar might be. Instead, he fills this self-love with content: “Dreams of reality’s peace/ Blow steam in the face of the beast/ Sky could fall down, wind could cry now/ Look at me, motherfucker, I smile.” Here, the speaker is realizing the confidence in the face of pressure that 2Pac often expressed, the same confidence that will propel the butterfly-consciousness into emergence.

That revolutionary idea first arrives at the end of “i” in an a cappella verse Lamar delivers (after ostensibly breaking up a fight at a show). “2015 niggas tired of playin victim dawg… since Tutu how many niggas we done lost… this year alone?” he asks the crowd. Seeing an opportunity to drop knowledge, he launches into a diatribe on the meaning of the n-word: “N-E-G-U-S description: Black emperor, King, ruler, now let me finish/ The history books overlooked the word and hide it/ America tried to make it to a house divided/ The homies don’t recognize we be using it wrong.” Lamar flips the script on it, taking a word once used as an epithet for a slave — three-fifths of a person by the constitution — and transforming it into the very symbol of mastery, the black emperor, a title given perhaps most notably to 20th-century Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie I. Lamar then tells us “black stars can come and get [him],” punning (hat tip to Genius commenter quannage for the catch) on Garvey’s Black Star Liner, the ship he proposed to take African-Americans back to their home countries.

Having realized the righteous power within himself, calling himself “realest Negus alive,” change is becoming possible for Lamar and the culture. Suddenly, the Boris Gardiner (himself a Jamaican) sample that opens the record comes into focus: “Every nigger is a star.” The butterfly rises, slipping through the cracks as “the four corners of the cocoon collide,” revealing that he is something greater “than what they analyze.” Returning to the beginning of the album, the revolving cycle of revolutionary consciousness begins anew amid the cracks and pops of the Gardiner record, the butterfly, now free from the cocoon’s shackles and speaking directly to the caterpillar that’s trying to pimp him. His hidden consciousness is the consciousness of the we, which includes all black people, dead or alive.

Mortal Men, m.A.A.d Cities

“You wanna love like Nelson, you wanna be like Nelson/ You wanna walk in his shoes, but you peace-making seldom/ You wanna be remembered that delivered the message/ That considered the blessing of everyone, this your lesson for everyone.” As To Pimp a Butterfly draws to a close, after the speaker comes to understand his potential as a leader on “Mortal Man,” Lamar reveals the final lines of “Another Nigga”: “Made me wanna go back to the city and tell the homies what I learned/ The word was respect/ […] If I respect you, we unify and stop the enemy from killing us/ But I don’t know, I’m no mortal man, maybe I’m just another nigga.” Respect (note: not respectability) is the necessary prerequisite for unity, the butterfly’s wings. Lamar uses respect to access a unified consciousness where he can speak with the spirit of 2Pac (maybe up in 2Pac’s “Thugz Mansion”), his ancestor in hip-hop.

What Pac tells him is nothing short of prophetic: “The ground is going to open up and swallow the evil… The ground is the symbol for the poor people, the poor people is gonna open up this whole world and swallow up the rich people.” You reap what you sow. The evils of Lucy, the greedy capitalist, will be swallowed up by the poor once they realize the sovereignty inherent in the ground. 2Pac lets us know that this will start with bloodshed, because once materialism (“grabbing shit out the stores”) becomes a tired exercise, the bloodshed of the oppressors is inevitable. “It’s gonna be Nat Turner, 1831, up in this motherfucker.” Neither 2Pac nor Lamar explicitly endorse this violence in the interview, but they both see it coming. Without significant structural changes to relieve the building pressure, all it takes is a spark to set it off.

2Pac never got to see changes (I recommend actually listening to that song again), but he implies that his spirit is working through Lamar to get them done: “Because it’s spirit, we ain’t even really rappin’, we just letting our dead homies tell stories for us.” He’s responding to Lamar’s statement: “In my opinion, only hope that we kinda have left is music and vibrations, lotta people don’t understand how important it is. Sometimes I be, like, get behind a mic and I don’t know what type of energy I’mma push out, or where it comes from.” Music can be a force that transforms us, awakening the consciousness within us by harnessing the power of the spirit that moves us. Hip-hop can be a world-changing, uniting force, but it has to see past the game, past mere materialism, while still communicating its reality to the awareness. Underlying To Pimp a Butterfly’s system of contradictions is a narrative of hope against the brutality of the systematic destruction of the unity of the culture, the murderous cops and the drug wars — that hope is in the possibilities of consciousness, that ever elusive revolutionary power that makes us all rulers of this world. For K.Dot, 2Pac, and all kings and caterpillars, my liberation is bound up with yours, and this is my last word: respect.

More about: 2Pac, Kendrick Lamar