When I was a little thing, I wanted a million Brannock devices.

When you’re a little thing, a million is incomprehensible — if you asked a little thing what a million things looked like, they’d probably describe what a hundred looks like. Which honestly is enough of most things, a hundred. If we let our little things mete out how many things each person got to have, the disparity might look more even.

Still, I wanted a million Brannock devices. I didn’t know they were called Brannock devices, but I was fascinated by them. You might not know it’s called a Brannock device, but you’ve probably used them. Maybe you were a little thing once, and you were taken by the hand into a shoe store in a mall like I was. “I think her feet grew” or “his old ones don’t fit,” a thing bigger than me said. So the Stride Riter brought out a Brannock device, the international industry standard for measuring the length, width, and arch of a foot. I was hooked.

Like lots of imagined solutions to daily problems, the Brannock looks stranger than its purpose. There are too many numbers, for a start, and lots of indecipherable lines. There’s a place for one of your body parts, but it doesn’t look particularly welcoming, especially when the moveable sidings and knobs are turned to box in your foot. They’re also peculiarly gendered, some proudly emblazoned with “SPECIALLY DESIGNED AND CALLIBRATED FOR THE CORRECT FITTING OF MEN’S FOOTWEAR” and others “COMBINATION MODEL.” Almost as a dare: what would this thing tell me about me?

The strangeness of the little device was entrancing. I’d collect them into my arms as soon as we walked from mall ambience into shoe story Velcro smell. I wanted a mountain of them, to see them oddly stacked, all the places for heels, none of the feet. I would imagine fitting both of my feet on a single Brannock. “You’d have to break your legs,” a big thing told me once. But what if I could bend them? A million Brannock devices for a million different feet.

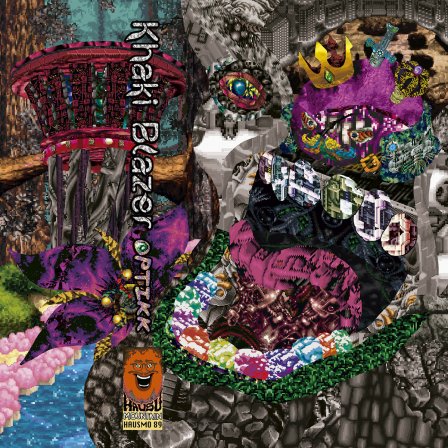

If you can imagine a million different feet, octopus-style, a million brains in their toes, you can imagine a little of Optikk. It is all your alls belonging to us. Listening to it is spilling all your alls everywhere. It’s less listening to every sound than a system of seeing you have to misspell if to write it at all. Optikk, all these feet, is Khaki Blazer is Pat Modugno in giddy knell mode, signaling a simultaneous end and beginning to listening. It’s shapeless in that it’s every shape.

It isn’t new shape — its endless restless sampladelia is too much of everything you almost know to be a cohesive gesture of new thing. A million feet, a lot of limbs to wriggle. It’s still shaping. Don’t try to measure it.

Because I always take for granted that the sounds on the record are still, or at least dependable; I can turn and return to songs and excavate more from them, but their everything’s always been there and will be, intact. Khaki Blazer’s sounds melt and morph every time I return to them, both in response to what chirped immediately before and what I brought with me. What is that sound on “Gabby”? Or: what will it be next time? You’d need an infinity of feet to footwork to this. Of course, you already have all the feet you need.

Maybe it’s because 2019’s literal boxes of actual people has scared me enough to medicate via Paper Mario, but Optikk is listening like video gaming. It is endless outcomes in a cartoon system whose very existence depends on you. You could lose yourself in the glitch of the thing, of tracing out where clarinets and clavinets and blurps and wheestles rub against each other to make *song*. But like a video game, Optikk exists as a singular text. It is an imaginary solution to a daily problem that looks stranger than its purpose. Modugno’s compositional ambition to marry cacophonies and symphonies in single breaths should not be taken lightly. Optikk is a bold next step in the Khaki Blazer project. I laughed at the arguing marching/toy train whistles of “Stand Up Comedian Bass” as much as I carbopped to “4/4.” Optikk is funny and funky. It successfully incorporates the occasional drone pathos of 2017’s Didn’t Have to Cut in ways that bowl me over each time the skronk of “VR Mr Potato Head” exits. It’s all the freed jazz impulses from Modugno’s Moth Cock outfit as an RPG avatar walking endlessly into a video game wall, giddily bucking levels and linearity, but always still walking

Like the namesake of “Black Mesh,” this material covers lots of legs. That material, the plunderfound device of Khaki Blazer, is a mostly-opaque assault of everything but: every now and then, the fabric runs right up against the outline of the thing. Which is your body, your leg, your million feet. And for a moment, you can see through the material. You writing about sounds is a body writing about its self, memories like the million times its feet moved or stood or shook. Writing words is such a backwards device for describing bodies and selves, in motion, at peace, transforming, cadavered. We measure little feet, and we police where they go. What if words are just more boxes? Do we need to invent more or less?

I was watching the 2019 homerun derby on mute this year, listening to Optikk. Like Khaki Blazer it was an exercise in collaging, but it wasn’t collage. Every time Vlad Guerrero Jr. barreled up a baseball, a little part of me shaved off in the combustion. Vlad Jr. was hitting baseballs in Cleveland, Ohio. Khaki Blazer is Pat Modugno from Kent, Ohio. One of those facts doesn’t impact the other. But there are lots of miniature combustions on Optikk. Some of them squelch and some of them pop, and in each one, a part of me shaves off.

What’ll be left? What’s already there? Or: what is the daily problem we’re imagining solutions to?

Whether the cartoon footwork of Khaki Blazer and Paper Mario or the crucial tension memory of a being little, of soaring through air, our artifacts of joys are highways by which we must invent the future. They are not artificial, and the joy is not coincidental, but the problem we face (again, as always and still) is the policing and box-making from those with a million things looking only for another million things. The imaginings are myriad and beautiful, but they do not cancel out the problem, which is simple and daunting; the problem must be dismantled through action shaved through with joy. Optikk, in its restless all-ness, is a ferocious reminder that we can unbox each other with careful relistening and deference to little things. Optikk, in the way it depends on ears to laugh and swing by, mourns what was, as it imagines what comes next.

A million feet can cover a lot of ground. Keep ripping down rules.

More about: Khaki Blazer