Hype is to the internet as a loaded gun is to a stage play: any good crafter of narrative will make sure it goes off as spectacularly as possible. The orchestrators of internet hype, of course, are the various bloggers and review sites (hopefully, this one included) who spot good things coming and then decide how they turn out. Of course, the metaphor breaks down, because artists, unlike characters, are chasing that loaded gun, always trying to grab hype and point it every which way in order to control it.

Rain in England is the first attempt by ballistics expert Lil B to point the loaded gun directly back at people like me. When I first heard that one of the teenagers from The (Wolf)Pack, who made one of the all-time great summer jams, was breaking out on his own and sampling Elliott Smith while rapping about blowjays, I was ready to throw the dude a parade almost before I heard his music. I checked the sketchy but intermittently brilliant “The World’s Ending” and the genuinely stunning “We Can Go Down” among hundreds of other freestyles and videos, and started making plans to fly to San Francisco to write a 12,000-word essay on ‘based music’ for Granta. Here, it seemed, was a guy with a genuine street sensibility, who was also into really weird, fringey sounds; for nerdy rap fans, it was like blood in the water.

So, I’m one of the hundreds of hungry sharks you can blame for how bad Rain in England is. From the title to the beat-less music and pure freestyle-poetry format, this is an album aimed squarely at punk-noise-loving internet tastemakers. It replaces weird samples with ambient backing tracks and dispenses with hooks and song structures altogether in favor of pure flow. The first problem is that the backing tracks are utter garbage. I don’t know whether Lil B made them himself or had someone do them for him, but maybe I’d rather not know. They sound like they were all produced in the two hours immediately after someone bought a Nord Lead at Guitar Center; they’re pure, unstructured noodling, occasionally out of key, with no overdubs.

That doesn’t mean the album isn’t conceptually daring. Although it’s been done, the idea of a beat-less hip-hop album is still pretty out there, and Lil B is uniquely equipped to pull it off. He’s partly known for his hundred variations on the theme of “Hoes on my Dick ’Cause I Look Like ____,” but the reason he really set the hype machine on fire is that he’s also got a poetic, philosophical streak a mile wide and a sincere intensity that’ll make you care about what he says. His lyrics, the center of this album by default, are not particularly tight or witty; actually, on his more ‘mainstream’ tracks, he runs toward the painfully obvious and even intentionally dumb, and as we’ll see, that’s been crucial to his rise and (momentary) fall. But here, really indulging his intensity and his non-style of repetition and simple concepts, he can come off weighty and profound. Leadoff track “Birth to Life” is a sterling example of the power of understatement, with B commanding listeners to “Just breathe… Celebrate life.” And on the next track, when you hear him declare “I want everything,” with droll seriousness, three times in a row, you’d have to be dead inside not to think Lil B is speaking for the human race and its bottomless well of desperate need.

But those two tracks might just stand out because they’re at the beginning, rather than at the end, of what turns out to be a painful slog. The tracks on Rain in England are completely indistinguishable from one another musically, and most of them are five or six minutes loooong. Many if not most of the raps are clearly freestyles, and while they’re pretty amazing for freestyles, most aren’t conceptually unified enough to provide the variety the music lacks. Worse, before long the idea of Lil B as an enlightened sage is overpowered by the reality of him as a self-important Holden Caulfield with Lessons to Teach the World. “Earth’s Medicine,” an extended riff on how the earth is sick and Lil B is the doctor for its ills, is an inescapable reminder that he’s from San Francisco: “Red cells is Navy/ White Cells is Army/ Took the temperature, volcanic…/ I think the Earth is a woman/ Mood swings represent seasons/ Autumn is awesome.” Ultimately, the long pauses would do more to increase his contemplative gravitas if they weren’t filled with juvenile keyboard noodling.

But isn’t it surprising that a musician who is smart enough to pull off such a net-hype coup in the first place couldn’t figure out that carpet-bombing the web with freestyles from 500 different MySpace accounts doesn’t necessarily mean that the music would make for much of an album? Of course he could; what he apparently couldn’t do was resist the fat, slow-moving targets that loved him for the more abstract end of his music. After he popped up and started getting real hype from the indie rock press, his backing tracks got increasingly left-field and trendy, culminating just a few days before the release of this album with him freestyling over the hazy, abstract sounds of How to Dress Well. Rain in England is his attempt to be what we wanted him to be.

And the worst part is that the hype he was pandering to is a kind of complex backhanded racism. Since I’m one of these nerdy indie/hip-hop critics, I’ll tell you what it’s all about: We, the mostly white and uniformly overeducated musical neterati, generally love three things; we love sophisticated musical boundary-pushing from fellow smart, educated, mostly white leftists, like Animal Collective; we love post-backpacker rap made by upwardly mobile, educated (mostly black) sophisticates like Kid Cudi; and we love ‘street’ artists like Lil Wayne.

The problem, of course, is that when I say ‘street’ music, what I mean is artists who are ‘really’ black — who talk, walk, and act like poor dudes from the inner city. And while frequently we’re classy enough to pick artists who are actually great — Wayne, Cam’ron, Eightball, and MJG — it’s also obvious that their main purpose is to provide some of what bell hooks describes as “spice” for the bland, middle-class whiteness of our lives. Ten years after hip-hop peaked commercially, it’s inescapable how much indie rockers, whose identities are tied up with seeming smart, love to watch the new-wave minstrelsy of black rappers talking and acting dumb. Through these sorts of artists, we can live out our fantasies of masculinity, violence, grandiosity, and unrestrained self-gratification.

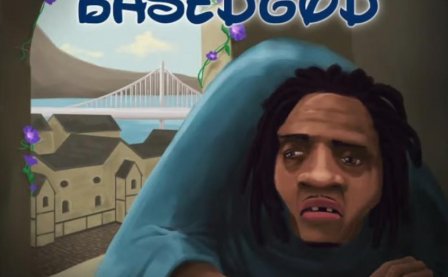

Of course, we also can’t really connect to them. We can imagine having a conversation with Kanye or Drake, but Wayne? We love to laugh at stories about his candy-eating excess, but he’s such a cartoon he barely seems human. That was the promise of Lil B: a kid who oozed I Want It All street hunger and uncalculated energy, who was too young to have gone to college even if he’d wanted to, and who yet apparently had heard a Brian Eno record at some point. He was, as the cover of Rain in England suggests, The Savior who would produce Real Rap for Nerds Like Us. That already exists, of course, from Rammellzee to Dälek to Saul Williams to Mike Ladd; but those guys were simply too smart and self-aware to fulfill a certain sheltered, ignorant image of Real Blackness.

Lil B is trying to reinvent the wheel, unaware of any of this tradition, because internet tastemakers wanted him to, so that he could be both Really Black and Weird Like Us. And it turns out he’s simply not the Nerd Messiah; he’s creative and emotional and gifted, but at least right now, he’d do better making rap songs rather than ambient soundscapes. (And like the insane workhorse he clearly is, he’s released several other albums in the last few months, seemingly targeted at other segments of his audience.) He’ll make a solid record, or two or five, once he figures out who he is. In the meantime, we have Rain in England: the sound of a kid shooting himself in the foot while dancing for your amusement.

More about: Lil B