While first listening to …and then you shoot your cousin on a hot Sunday afternoon, I’m riding my bike down a familiar street only a few blocks away from the home in which I’ve lived for 18 years, and suddenly I’m completely lost. As Patty Crash’s light, lazy hook on “Never” contrasts rap motifs with the helpless feeling of being radically present, unknowing, and vulnerable (“Street dreams/ Close your eyes/ Say goodbye to my memory”), Arizona’s summer sun beats down heavily and obscures my vision. I struggle to navigate my hometown’s beige and meandering suburban neighborhoods. As the melancholy progression at the end of “Tomorrow” melts into the album’s final eerie, improvisational flourishes, I am beginning to get my bearings, and I’m now about half of a Roots album late for my friend’s grad party. Black Thought’s verses convey a contradictory sense of uncertainty and abjection shrouded within familiarity (his first lines: “I was born faceless in an oasis/ Folks disappear here and leave no traces/ No family ties, nigga, no laces”) not totally unlike the feeling of being lost in one’s hometown, which is why my first encounter with the album was unusually resonant and provoked further listening and exploration. Still, as was the case with their previous effort, undun, The Roots aren’t offering any simple and declarative thematic content through their latest, shortest, and most confounding concept rap suite.

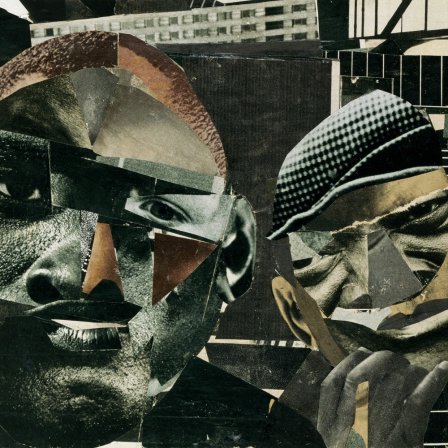

At the end of this site’s review of undun, Nick Philippides suggests that the album would have been stronger as a narrative-based work had Black Thought’s lyricism painted a clearer picture of the situations, characters, and locales to which that album’s story was referring. Instead of honing in as a band of faithful raconteurs, The Roots have disappeared even further into ambiguity here — Black Thought called the new album “satire” and recommends multiple listens. While it was relatively easy to tell when Thought was rapping “in character” on undun, here it seems like he’s never or always “in character,” depending on how rich and explicitly bracketed-out you consider this record’s cast of characters to be. The people whose voices seem to be telling these stories are as indefinite and flexible as the characters portrayed on the Romare Bearden collage used as LP art; cut-and-pasted together from varied impressions of individual voices and experiences until the resultant figures are wholly impossible, irreducible caricatures of black America. While Thought assumes multiple roles (a “sex-addicted introvert” on “When the People Cheer,” a no-bitch-loving bullshitter on “Black Rock”), frequent collaborators Greg P.O.R.N. and Dice Raw play along, respectively assuming Lil B- and Trinidad James-esque flows for relentlessly smart verses. Even when Thought’s satirical project falls apart and he seemingly raps as himself, his lyrics are funny and referential to the work of more mainstream rappers like Nas and Jay Z (to say nothing of the KRS-One reference in the album title). The only moments on the album (including the sampled interludes) in which lyrics seem to be a distraction from rather than an instrument of the band’s conceptual aim are on a few of the many guest spots (see Mercedes Martinez on “The Coming,” whose vocal contribution ends up seeming superfluous and vaguely like something pulled from a two-hour YouTube vocal trance mix).

Sonically, The Roots have prepared a mixed bag of techniques dependent in large part on pianist D. D. Jackson and the interpolation of unedited jazz and R&B samples. Avant-garde composition and free-jazz improvisation appear most prominently on “Dies Irae” and “The Coming,” where they are deeply effective in conveying a hopeless and confused tone to complement Black Thought’s flamboyant lyrics. Still, the cramming of musique-concrète producer Michel Chion and Jackson’s contributions together in the middle of the album seems to endow them with less individual significance than they deserve, and one can’t help but feel that a more even dispersion throughout would have been appropriate. On the other hand, ?uestlove loosens up and plays with unfamiliar abandon on tracks like “Black Rock,” making this album a prime example of his tight organization as a bandleader and musician in his own right.

The prevailing narrative regarding The Roots places them at the center of a contradiction; they engage in nightly banter on one of American television’s most coveted timeslots, but they still aren’t afraid to play Fishbone’s “Lyin’ Ass Bitch” as walk-on music for Michelle Bachmann if it means a tongue-in-cheek assertion of identity. They’ve constructed a logic in which straightforward, indie rock-inspired conscious rap albums like 2010’s How I Got Over can coexist with the focus and artistic seriousness of undun. This is a logic in which a band like The Roots could easily find themselves trapped, as they strike a pragmatic and unmoving balance between mainstream and avant-garde aspirations. Even though …and then you shoot your cousin never quite betrays its allegiance to either criticism or satire and is consequently an awkward, variable amalgam of both, it offers something important in its efficacy to disrupt that logic and pave out a new line of progression for a mature act.

More about: The Roots