We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

With execution, murder, and politics, with a hint of lust and a one-party power struggle in the air, it could very well mean that Mr. Bo ends up on the cover of Fernow’s next album — surely he bears all of the credentials, in spite of how impossibly far apart these two stories might be. But that’s just the point: they are probably as relevant to one another as the shooting at Fort Bragg was to Prurient’s Caribbean Overdose before a desire to expose curiosity for the macabre led to an intriguing approach to cover art. What remains of interest is not only how a deliciously productive musician has entwined himself with macabre affiliations and abominable world events through creating his own peculiar little niche genre of techno with a shock junkie aesthetic, but how the passing of major artists can go relatively unreported when the circumstances are not quite as stirring.

Despite the undemocratic nature of the Chinese political system, it still has the potential to encourage full and flagrant responses to injustices exposed, which provide a captivating context for observing innovative dissidents who remain stranded in such political predicament. Josh Feola is responsible for the fascinating 100 Flowers column on TMT, which he recently used to discuss the work of Yan Jun, who has been able to operate as a pioneering sound artist throughout China without patronage, while his contemporary, in-house dissident Ai Wei Wei, took to protest, dancing “Gangnam Style” in a pair of handcuffs, a video that was almost immediately censored in China after being uploaded online in October.

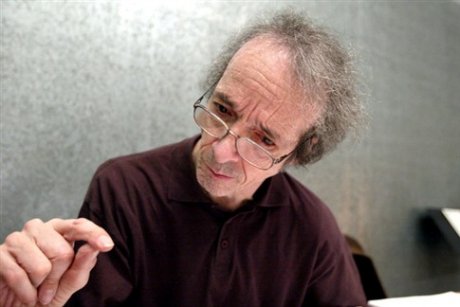

The reaction to such political circumstances ranges dramatically across the board, and while the CCP was gaining momentum in quashing mass revolt all over Tibet in the 1950s, the Estado Novo was wreaking havoc right through the Iberian Peninsula where Emmanuel Nunes was studying at the University of Lisbon. The Portuguese regime made it so difficult for the young musician to continue his studies in classical scoring that he was forced to take private lessons from Communist party member Fernando Lopes-Graça, who eventually persuaded Nunes to move to Paris, where he lived intermittently until his death earlier in 2012. One can not be sure if it was due to an absence of murder and lust that was lacking in the Portuguese composer’s death, but the occurrence went devastatingly unreported in international press. The man was an extraordinary musician and one of the finest avant-garde practitioners of the last century, who successfully crossed the border between electronic investigation and what would now constitute contemporary classical art forms. He passed away in September, leaving behind an stupendous legacy of wonderfully gloomy experimental scores. Never a man to stray from the macabre, one of his most recent pieces embodied a musical interpretation of Dostoyevsky’s A Gentle Creature, the tragic tale of a young girl driven to suicide by her disdainful older lover. Regarding his orchestras, Nunes was always keen to emphasize that “it is more important for me to know what I do not want, than for me to know what I want.” In the case of his later recordings, he proved to be an artist who took little delight in creating cheerful and prissy art, but his avant-garde scores continue to maintain their brilliantly haunting air.

Emmanuel Nunes. Photo: Arquivo Global Imagens

Emmanuel Nunes. Photo: Arquivo Global Imagens

The feel of compositions such as Nachtmusik is distinctly eerie, exposing a tendency for adopting plot lines and inspiration from doleful Russian suicide novels. The macabre angle is a factor the audience experiences atmospherically. Nunes’ breathtaking orchestras and grandeur chamber music create tangible listening environments within their sonic embodiments of the themes explored, and this is an essential component to the darkness that sound alone is capable of conjuring over a plethora of genres. When Nathan Shaffer interviewed Locrian and Mamiffer back in Feburary about their then forthcoming release Bless Them That Curse You, similar points were made during a discussion about song titles and the forlorn themes that run through that extraordinary collaboration. Faith Coloccia of Mamiffer reflected on the sonic representation of ritual and the manner in which states become altered through separation and decomposition, pulling on ideas concerned with tarot readings and divination, influences that could not be more apparent on the album as a whole. Such concepts are aurally transfigured into lengthy, bludgeoning pieces that stir up some wonderfully macabre imagery; sustained bass guitar drones fed through unrelenting hiss and submerged vocals, an inevitable ceremony lament ebbed across six tracks that pertain to an artistic drive for exemplifying an irrepressible gloom. The track titles are indeed indicative of the aesthetic nature of the music; “Second Burial” kindles imagery of that very act, and it is dealt with in a fashion that would generally be considered tasteful and discreet in its tackling of a subject so often deemed taboo — representational of memory, reflection, and commiseration.

Free Exhibition on the Motoyasu River!

The avid presentation of guts-on-screen and the graphic savagery that might be associated with horror genres, grindcore, and death metal has been substituted here to focus on more powerful images. Rampancy and extravagance merely disfigure the occasional inclination one might share in watching a slasher film or listening to Pig Destroyer, credulous hyperlinks for a macabre fix that demand a specific context in order to fully provide any desired affect, and for over 40 years, Kaneto Shindo proved to be inexplicably masterful in assembling conditions that undoubtedly delivered the goods. Although he died in May at the age of 100, this treasured director experienced a life of great misery and tumult, which was brought out in some of his most celebrated works. Perhaps his most renowned film, Children of Hiroshima, returns to events commemorated sonically by Krzysztof Penderecki in his threnody, the damage and struggle of civilians affected by atomic fallout and the livelihoods that were destroyed as a consequence. Shindo’s projects are visually uninhibited through their focusing on disfigurement and incineration, themes that were revisited later on in his horror films of the 1960s, specifically Onibaba, which seizes upon the torment of mutilation in scenes that have been inaccurately described as “otherworldly,” a description often attached to depictions of the macabre, particularly when the subject remains so distant in its abject terror.

Shindo’s productions drew from personal experience as well as survivor accounts from actual occurrences. Each enterprise was thoroughly researched and re-imagined for global audiences, who became susceptible to grim reminders that uncompromising degrees of truth lie in what his audience was subjected to. This lies at the very forefront of what the macabre has always stood for: a documentation of gruesome truths as a means for release, sacrament, commemoration, or remembrance. To think that these themes have continued to exist so pressingly over time is quite astounding, though they are also a constant reminder of the harsh realities that inspire them. Baline Harden published his Escape from Camp 14 earlier this year, a book that saw him working side by side with Shin Dong-hyuk, the only individual known to have been born and then to have escaped from a North Korean gulag. It is without question a harrowing read, one that forgoes any doubts about the cruelty expressed in Shindo’s vision; the deaths that occur in these camps go unseeingly marked by any bout of concession or remembrance that would trigger refracted emotional disappearance or sense of loss, for even the glibbest funeral march has the potential to kindle flames of remorse and revenge that give rise to fires of discontent, protest, and rebellion.

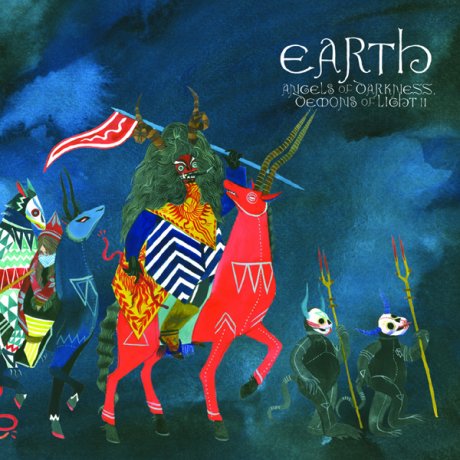

Cover art for Earth’s “Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light II”

Cover art for Earth’s “Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light II”

Regardless of the form it takes, procession and ceremony instigate recollection charged with feeling, a combination destined for collective commiseration that is equally as essential for the battleground. When Stacey Rozich first brought her cutthroat effigies to life for Earth’s Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light I, a victor was framed standing behind the slain, an incarnation of Liu Bei triumphs over a Nian lion, both are depicted equipped for battle — horns sharp, tongues hissing, and paper-chain entrails gushing — a wonderfully striking image that operates as scaffolding for the tumbling gothic rock that pours hence. This year’s follow up features a comparably heroic representation: marching Taotie characters; a smokey, hued twilight; and an entourage of fabulously decked-out miscreants. The album pitches death as an unstoppable force against the sluggish drench of the music it harbors, an unmovable object. A synthetic funeral dirge packaged in its own sedation, a cascading demise of wispy triumph that crystallizes the very essence of the macabre through its surly and beckoning expiry.

In a subjective sense, Angels of Darkness left a disjointed mark on the works compiled by some of the artists who died in 2012 — the husky, dramatic scenes of tribute conjured by Kaneto Shinodo or the strategic reflections of Po and Lovecraft in Škvorecký’s The Engineer of Human Souls. Indeed, Škvorecký’s style was esoteric and gruesome, but it came with such large doses of humor that it was possible to shrug off the mini-tragedies that took place within the worlds he spun throughout his writing. It exemplified macabre as a feedback loop that complemented the author’s struggle in opposition to the daily grind, an exemplification of how the writer used uncanny situations concerning his upbringing to further beautify the efforts of other writers and artists who impose themselves on the characters they create, who in turn have about as much in common with each other as, say, Shin Dong-hyuk does with Jonny Greenwood. As an estranged collection, the handiworks rendered within constitute a depiction of apprehensiveness that remains universal, particularly when taking into account the constantly evolving approaches to communicating personal tragedy, death, and decay. Through various formations and styles, these artifacts typify a fresh body of material within an exhibition that only continues to expropriate and contort, uninterrupted, as another year draws to a close.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series