paracosm n. A prolonged fantasy world invented by children; can have a definite geography and language and history.

The Modernist reading of Picasso’s early-20th century Analytic Cubist period asserts that, by deconstructing the fundamental artificiality of traditional, perspectival representation — by tearing down and challenging Western painting’s prior focus on the realistic emulation of three-dimensional space — the painter began to assert the literal flatness of the painting’s surface, emphasizing the true, tangible materiality of the canvas rather than any sort of illusionistic, constructed space. And yet, even as Picasso’s works increasingly challenged traditional notions of form and depth, the painter refused to let them fall completely to abstract flatness — refused to completely let go of the last shreds of representation remaining in his work &mdsah; by inserting trompe-l’oeil illusions that suggested three dimensions; why? Perhaps he feared that, if he were to paint a work of absolute flatness — a work containing no reference to illusionary, constructed visual space, no matter how fleeting and insubstantial that reference might have been — then his art would suddenly become akin to meaningless, superficial decoration: flat wallpaper meant to appease the eye but not stimulate the mind.

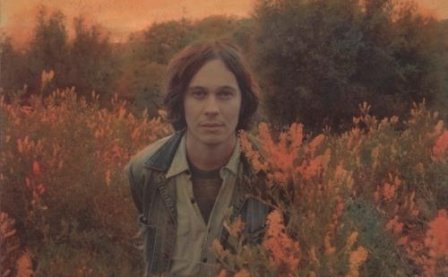

It’s an understandable fear. I usually operate under the assumption that most artists — even those who explicitly aim to create something pleasant for the beholder — hope that, at least on some level, their works possess more depth and resonance than that afforded by mere prettiness. Washed Out — the moniker of Georgia producer Ernest Greene — is certainly one such musician who aims for outright beauty. From the lo-fi electronic pop of the Life of Leisure EP to the more expansive- (and expensive-) sounding Within and Without, Greene has proven himself adept at crafting consistent — if somewhat monotonous — songs that conform to the sound of that now-infamous aesthetic that arose in the late aughts. Greene now returns with his sophomore album, Paracosm, a record that, in relation to its predecessors, seems to float in a sort of aesthetic stasis not unlike the feeling that Greene’s songwriting often induces.

Indeed, while Paracosm has arrived packaged in talk heralding its comparatively analog production process, let’s be honest about the material at hand: Ernest Greene is still tapping into the exact same vibe as his prior work. “Dreamy,” “Balearic,” “snowy,” “lush,” “wispy” — these are just a few of the adjectives used by critics to describe Within and Without that I unearthed in merely two or three minutes of searching. And that’s fine; he’s doing this sound just as well as he always has (which is to say: very well). But part of me can’t shake the notion that Greene’s primary goal with this new material was to conform to the very aesthetic that he helped define with his undeniably inspired early material.

And yet, I can’t really bring myself to tear this thing down critically, for — if my unsubstantiated surmisal of Greene’s intentions was correct in the slightest — Paracosm succeeds absolutely at the project that it undertakes. On a purely instrumental level, the record sounds remarkably solid, offering a near-constant stream of sonic flourishes — from the opening vibraphone and harp of “Entrance” to the guitar and field recordings that frequently crop throughout the remainder of the record — that highlight Greene’s uniformly warm production. And the melodies are as achingly pretty as ever: first single “It All Feels Right” and the mid-album twosome of “All I Know” and “Great Escape” are some of the most unshakeable earworms yet penned by Greene. In other words, all of Paracosm’s moving parts combine to create a slick product that will undoubtedly satisfy Washed Out’s average customer. The aural hallmarks of chillwave are all present here, and their amalgamate is, as ever, an Instagramian sense of instant, (ahem) washed-out nostalgia.

To be honest, I’m not sure that Greene ever intended for these songs to be anything other than “dreamy,” “Balearic,” “lush,” “wispy” pop tunes, consistently pretty and easily digestible. He’s tapped into a sound that continues to be eminently marketable — a sound that he’s arguably doing better than anyone else. Paracosm certainly does see some minor tweaks to his aesthetic, but at this point, it’s clear that the artistic trajectory of Washed Out should not be likened to the more meaningful progressions of some of Greene’s contemporaries (looking at you, Chaz). Rather, Greene has found a sonic world — a paracosm, if you will — that he’s incredibly good at mining. Sure, I can’t help but think about Picasso’s fear of his art becoming mere decoration, meaningless wallpaper, but Paracosm is, at the very least, beautifully rendered wallpaper, and it’s hard to blame Greene for living in this fantasy for as long as he possibly can.

More about: Washed Out